March Madness! That phrase is the usual rallying call of the NCAA men's basketball tournament each March. Millions of people idle away hundreds of hours filling in brackets, watching the games, and crying about how one upset or another ruins their chances of winning it all. But this month, we saw a different kind of madness, one whose origin is in financial not educational circles and whose ‘upset’ threatens more than just bragging rights and modest windfall from the office pool: the sudden spate of bank crises that have captivated headlines throughout this month.

It all started in early March with the announcement of a voluntary liquidation by Silvergate (3/8/2023), followed by the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) (3/10/2023) and Signature Bank (3/12/2023), and topped with the news of the forced acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS (3/19/2023). If one were superstitious, one might suppose that the fact that all these bank crises involve firm whose name beging with the letter ‘S’ (Credit Suisse means Swiss Credit in English) is just the way that the universe selects the banks to fail much in the way that people select NCAA Tournament winning teams by uniform color or mascot name. In fact, it isn’t superstition but rather underlying rules of economics which led to these failures, even though each has as its proximate cause that is somewhat different from the others. The following table summarizes the proximate causes and points to additional resources (Wikipedia (W) and/or the appropriate video(s) by Patrick Boyle and Plain Bagel (v)) for further explanation and unpacking.

| Bank | Proximate Cause of Crisis | Additional Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Silvergate | Bank run caused by downturn in the cryptocurrency market following the dissolution of FTX, one of their largest customers, resulting in a 70% loss in deposits and exposure to an unhedged interest rate risk | |

| SVB | Liquidity crisis due to poor risk management of interest rate vulnerability and a bank run | |

| Signature Bank | Closed by the New York State Department of Financial Services due to its exposure to the downturn in the cryptocurrency market | |

| Credit Suisse | Liquidity crisis triggered by inopportune language by one of its large investors coupled with its ‘bad boy’ reputation |

In the case of the three US banks, exposure to cryptocurrency and an either direct or indirect vulnerability to interest rate changes are, in essence, what caused their collapses. Building on the analysis of Patrick Boyle (e.g., Bank Runs! What's Going On?), these banks found themselves, like other institutions, awash in deposits during the pandemic. Some of this great influx of cash was due to pandemic relief measures that were perched on the Federal Reserve’s expansion of the money supply and some of it was due to the lowered economic activity as most people endured lockdowns.

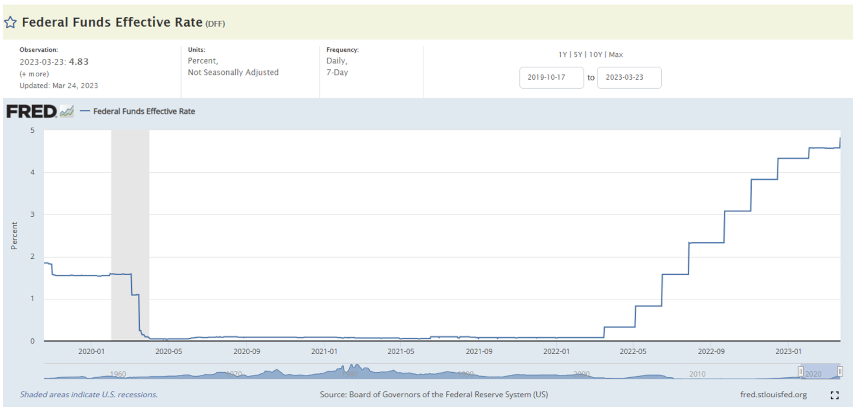

Once a bank sees a marked influx of deposits, the next question is what to do with them. A bank’s job is to act as an intermediary to get unused capital from party A into the hands of capital-deprived party B; that is to say, they need to invest the available funds in the forms of loans. The number of initial public offerings and other start-up loans having fallen off left these firms looking for other places to invest. Since interest rates were effectively zero, these firms decided to invest their deposits in a mix of risky cryptocurrency, for their potential upside gain, and in long-term bonds, for their risk-free return and ability to meet the capitalization requirements each bank must comply with. This this might have been a safe strategy had not the Federal Reserve began diddling the economy by increasing the money supply and then by raising interest rates in a vain attempt to tamp down inflation.

When FTX collapsed last October there was a strong pressure for many depositors to exit their crypto positions. The following graph from coinmarketcap.com shows how the overall crypto market capitalization fell by roughly 10% over the days from March 8th to March 12th.

This, in and of itself, would not have done any of these banks had not the run on their firms also coincided with the Fed raising the Federal Funds Effective Rate sharply over the last year from essentially zero to 4%.

The end result was that two of the banks, Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank, had to generate immediate liquidity by selling their long-term bonds before they matured. With greater returns available to investors buying new bonds after the rate hike, both Silvergate and Silicon Valley Bank were left holding what were essentially value-less bonds, which they had to sell at a loss rather than hold to maturity. These losses, in turn, led to both firms with no way to recover with Silvergate voluntarily goinginto liquidation and Silicon Valley Bank being put into receivership.

The cause of the collapse of Signature was rooted in an overexposure to cryptocurrency. It isn’t clear from the available reports whether Signature was also caught between the cryptocurrency-rock and rising-interest-rate hard place, put even if there were no direct link, there is a case to be made that the very low interest rates during the pandemic meant that any firm investing in anything risky would be vulnerable to rising interest rates.

As of mid-March, the Treasury, the FDIC, and the Federal Reserve had assured depositors that they would be made whole, even if their accounts totaled larger than the $250,000 maximum insured by the FDIC.

Next month’s post will examine whether this ‘make them whole’ approach is reasonable or whether it opens a door for a host of moral hazards.