The Simple Facts about Unemployment

Many of my friends and co-workers don’t understand my concern about employment in this country. The unemployment rate has, after all, fallen from a peak of 10% in October of 2009 to the current value of 5.8% in November of 2014 (data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics). So, as the argument goes, what’s my problem?

Well, as I try to point out, the unemployment rate really doesn’t tell the whole story. It is only one measure of the health of the labor market, and not necessarily a good one. When there is a lot of economic growth, as in the eighties and nineties, the unemployment rate is a reasonable measure of the health of the work force. When the labor market is experiencing the type of new normal that the country is currently mired in, it is a poor measure indeed.

The reason for this is that the unemployment rate measures the percentage of workers who are in the work force and are actively looking for jobs but unable to be employed to the total population in the work force. What the unemployment rate doesn’t measure is the size of the work force relative to the population of the country as a whole.

This definition of the unemployment rate appears in both textual and mathematical form in countless articles and texts dealing with employment and the labor market. So does the caveat about the work force participation. However, I don’t know of a single place that illustrates these distinctions in an easy to calculate, visual form, and so I decided to supply one of my very own.

For the sake of this illustration, I am going to assume a static population, a snapshot if you will, and I am simply going to calculate percentages based on a visual representation of various components of the population. Also for simplicity, our population will be divided into four demographics: minors, college age, working age, and retired. The definitions for these four demographics are:

| Demographic | Definition |

|---|---|

| minors | The portion of the population too young to hold a job in the economy. |

| college age | The portion of the population that is old enough to hold a job but who may choose to opt out to attend higher education. |

| working age | The portion of the population that is past the age to attend higher education and is in its prime working years. |

| retired | The portion of the population that is past the age where it is allowed to work. |

Obviously these demographics represent a gross simplification of the actual population. There are never as cleanly drawn lines in the real case as there are in this ideal case. But to illustrate the point, these are close enough to make a good model for the economy and an easy model to understand the labor market. I’ll talk a little more about the complications after the basic model has been developed.

Let’s start with the ideal world shown here

Those members of the population that hold jobs in the economy are colored green while those members who are not in the work force are in gray. It is worth taking a moment to talk about what it means to be in the work force. Clearly the minors and retired demographics are not in the work force because they are not allowed to hold a job. All the members of the working age demographic have a job and so they are obviously in the work force. The only group that requires some thought is the college age demographic. In this ideal world this demographic is exactly split in half with two members opting into the work force and two opting to pursue higher education. With 24 total members of the population and 18 workers in the work force, the work force participation is 18/24*100 = 64.2%. The unemployment rate is zero since everyone in the work force is working.

Now let’s introduce some economic realism and assume that not everyone who is in the work force can actually find a job. This more realistic world looks like

where the members of our population who want a job but are unable to find one are now colored red. In this scenario, two workers from the working age demographic and one worker from the college age demographic are now out of a job. The number of workers in the work force has remained unchanged at 18, and so too has the work force participation, but the unemployment rate, which is a measure of the percentage of the work force without a job, has risen from zero to 15/18*100 = 16.7%.

Finally imagine that the college age worker has decided enough is enough and he heads back to an institution of higher learning, and that one of the unemployed working age guys decides to stay home and play video games all day long. These two members of the population have now exited the work force (colored gray with red trim to remind us that they were once in the work force), which shrinks from 18 to 16.

The one remaining unemployed working age guy keeps at it but is still unable to find a job, and the unemployment rate shrinks to 1/16*100 = 6.2%, reflecting only his frustration in not finding a job. The work force participation now falls to 16/28*100 = 57.1%.

Clearly the population as a whole is no better off with this lower unemployment rate than it was with the earlier case with high unemployment. In both cases, the number of employed workers in the population remains the same at 15. These 15 are now charged with producing the goods and services that will be consumed by all 28 members.

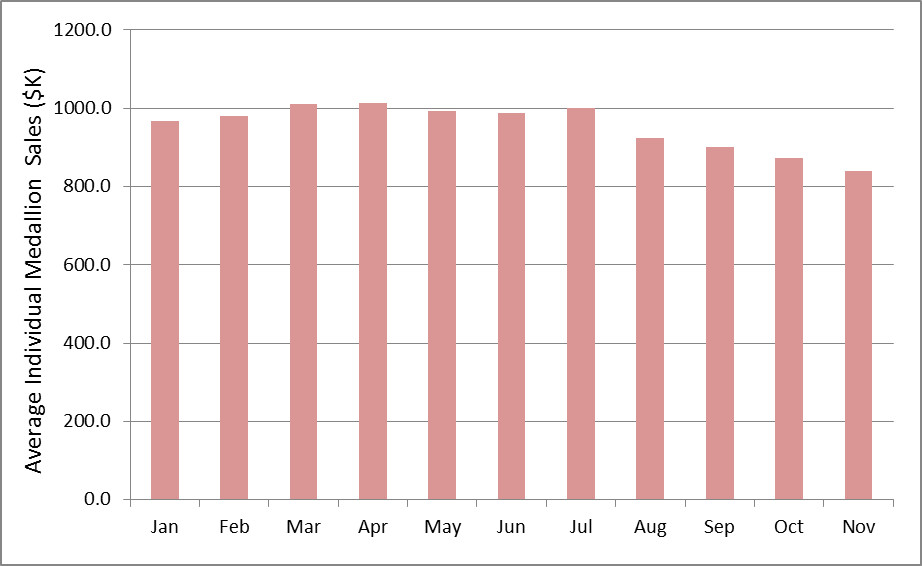

So, does this model actually represent reality? The unfortunate answer is yes. While the unemployment rate has fallen, so has the work force participation. Statistics pulled from the Bureau of Labor statistics for both the unemployment and work force participation rates result in

Of course, the US population is not static like the model problem discussed above, so maybe there is some way to reconcile a shrinking unemployment rate with a diminishing work force participation without having to conclude that there is trouble. Also, what about all this news that says that hundreds of thousands of jobs have been created each month?

The population of the United States was growing annually at about 0.7% in calendar 2013, which is the lowest rate since the Great Depression. Assume a base population of 300 million, which is a lower bound well below the actual value of approximately 317 million. The number of new births each month in 2013 was 175,000. Now assume that somehow this birth rate, in absolute terms, remained the same in perpetuity – that is to say that 2.1 million children would be born each year. This scenario is clearly unrealistic since the growth rate is measured relative to a growing population, so to achieve this scenario we would have to have ever falling population growth rates. In fifty years of such a growth model, the population would increase from 300 million to 402.9 million with the growth rate decreasing from 0.70% to 0.52%. Note that this model also assumes that everyone lives to retirement. Finally, assume that the country as a whole is content with a 62.5% work force participation rate.

None of these assumptions are realistic let alone likely, but by making them, we can calculate a lower limit on the number of new jobs needed each month just to keep the status quo. That number, of course, is 175,000 new jobs per month to match the birth rate. Now we can compare the actual job growth seen in the country over the time span from 2007 (the time when the country actually had about 300 million in it) to today against this 175K target.

Over this time span, a net 2.835 million jobs were created according to the BLS job creation numbers. That’s it! Barely enough jobs were created in 7 years to cover about 1 and 1/3 years of population growth in the anemic model discussed above, and probably not even a full year under realistic population growth. In order to get back to work force participation levels close to where we were in 2006, the last year where job growth approximately matched population growth, the country as whole would have to produce at least 14.7 million extra jobs in 2015. That’s over 1.2 million jobs a month – a far cry from the job growth currently hovering around 240,000 a month on average for the first 11 months of 2014.

So the next time you hear news about the rosy picture of the US economy based on the unemployment rate, take a moment, breathe, and think about all those poor souls who have given up looking for a job.