Tinkering with Equilibrium

The genesis of this week's column is mostly based on chance; a chance visit, a chance purchase, and a chance reading. Nonetheless, the end result is a nice example of how government interventions in a market can look good on the surface but have a less attractive side underneath.

Let’s start with the chance visit. Recently, I had an occasion to stop off at a used bookstore near a college campus. The basic function of this establishment is to buy back textbooks at a cheap price, resell the products back to others at the going rate for used textbooks, and to store the unwanted product as tastes and approaches in teaching and the professors who teach them change. The fact that the resell price is significantly higher than the buy-back price seems to irritate the bulk of the clientele (judged by my casual viewing of the interactions at the register). The reason for this cost differential – that this particular book store needs to pay for the storage of the books, the labor of the various people who catalog and handle the product, as well as the rent and upkeep of the shop – slips by the average consumer. And, although this column is not explicitly about this mismatch of expectations, the basic theme of the unseen cost is. Looking back in hind sight, these preliminary observations of mine were perhaps a foretaste of what fate had in store.

In any event, I began to wander about the store; an adventure in and of itself considering the vast number of abandoned titles piled precariously all over the floor. Training in the high hurdles would definitely be an advantage when browsing the inventory. Turning a corner, I came across the store’s collection of Schaum’s outlines. Overall, I am a fan of these do-it-yourself study guides. Not so much due to their teaching style, which is often minimalistic and confusing, but rather the vast number of worked problems that one can immediately dig into. The effect they produce is a lot like finding a bunch of how-to videos on YouTube with the convenience of the at-your-own pacing that books afford. Glancing at the shelf, my eye caught the title Microeconomic Theory, 3rd Edition, by Dominick Salvatore of Fordham University and, almost on a whim, I decided to purchase it for a mere $5 dollars (which goes to show that one can get a bargain if one is willing to settle for yesterday’s textbooks and study guides).

In odd moments, here and there, I began to dip into the outline and amuse myself with some of the questions and solved answers. Early on in the book, Salvatore goes to some effort to set the scope of the study to be strictly microeconomics. Interconnections of one market to the next are to be kept to a minimum. So I can’t blame him for what I found shortly thereafter but I thought it made for a good ‘teachable moment’ about ignored or unseen costs.

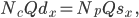

The scenario he explores is clearly contrived for pedagogical purposes, but I reason that if it is sufficiently illustrative to go into a Schaum’s outline, it is also sufficiently realistic to serve as a valuable thought experiment. In this scenario, the micro-portion of the economy that is being examined consists of 10,000 consumers and 1,000 producers of a particular product, which he calls ‘X’. For simplicity, each of the consumers possess the same demand curve given by

where  is the quantity demanded of for a given price

is the quantity demanded of for a given price  that they must pay. Likewise, each of the producers follows a supply curve given by

that they must pay. Likewise, each of the producers follows a supply curve given by

where  is the quantity they are willing to supply if they can charge price

is the quantity they are willing to supply if they can charge price  . The prices that the consumer pays and that the producer demands equal each other when the market is in equilibrium. The following figure shows the demand and supply curves for this market.

. The prices that the consumer pays and that the producer demands equal each other when the market is in equilibrium. The following figure shows the demand and supply curves for this market.

From the figure, the equilibrium point, where the two curves cross, falls at $3 and 60,000 units produced. We can confirm this result by solving the equation

where  and

and  .

.

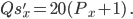

Salvatore then directs the reader to consider the case where the government decides to intervene in this market by providing a subsidy to the producer of $1 per unit produced. He asks:

Part (a) is a bit tricky to solve in that one must first decide what is exactly meant by a $1-dollar subsidy. In short, it means that the producer now perceives that he can charge a dollar higher than he could without the government intervention. Ignoring for the moment that the new equilibrium will move, the producer gets $4 when a consumer pays him $3 since the government is stepping in with an additional $1. As a result, the producer’s new supply curve is

Functionally, this looks as if the producer’s supply curve has been shifted down by $1 as seen in the figure below (the new, shifted curve is labeled ‘Government’).

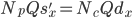

The new equilibrium is solved as before, and either direct inspection of the graph or algebraically solving

results in the new equilibrium of 70,000 units produced at $2.50 per unit. Salvatore then points the student to the conclusion that this government intervention has benefitted the consumer since price has fallen by 50 cents per unit. By analogy, this analysis also suggests that the producer is better off in that more units have been produced.

And this is where I got perturbed by the strict adherence to microeconomics. It is true that this market seems to have been helped but there are unseen costs that at a minimum could have to be discussed even if the implications to other markets were avoided.

Specifically, before the government intervention, a total of $180,000 dollars moved from consumer to producer in this market (60,000 units at $3/unit). After the government intervention, a total of $245,000 dollars moved to the producers in this market. It is true that the 10,000 consumers only shouldered $175,000 of that cost but it is wrong to ignore that the producers actually received $70,000 in government subsidies.

Where did that additional $70k come from? It is easy and tempting to say that it comes from the government and to stop there, but that misses the point. Where did the government actually get that money? Well it could have printed it or it taxed it. If it printed it, the cost of that action eventually comes back in the form of inflation, which devalues the consumers buying power, resulting in a new set of supply and demand curves. More likely, it taxed it, which means it took money from consumers, some who weren’t that market, and injected it into this market. It made some consumers reap a benefit at the expense of others suffering a loss.

Of course, this scenario is contrived but the logic and the lesson is not. The point here is that it is easy to see the direct costs and to ignore the hidden or indirect costs. As long as a citizen doesn’t dig too deeply, he probably never knows when he is being robbed blind.