When Cooperation Becomes Collusion

Life often offers us microcosms – little systems that we can examine that reflect the behavior of the whole. The economy is no different in this regard and often small behaviors and patterns found in a single market reflect larger ones found macroeconomically across the entire webwork of markets.

Case in point, the activities and behaviors found currently in academic peer review of scientific results give an excellent example of how cooperation is not always a good thing, demonstrating in concrete (albeit small) ways the wisdom of the old economic warning

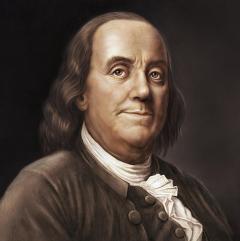

This adage’s attribution remains clouded in mystery with some claiming its origination with Benjamin Franklin at the founding of the United States

Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

while others maintain that it was said by Alexis de Tocqueville or even someone else.

It doesn’t really matter who uttered this maxim. Whether Franklin said this or whether someone else did or it just arose from the body politic, there’s no denying that it contains an essential truth about cooperation within the economy as a whole. Namely, that there is a distinction between the kind of cooperation that benefits all members of a society and those kinds of cooperation that benefit only a subset of individuals at the expense of everyone else.

Before delving into the problems with scientific peer review, let’s take a few moments to talk about the good kind of cooperation.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas has a nice discussion of cooperation entitled Free Enterprise: The Economics of Cooperation. They note that cooperation is desirable, since it pushes “back the limits of scarcity” but that the since scarcity is an unavoidable and fundamental aspect of all economies, competition will inevitably arise.

It is these two forces, when properly mixed, that create the positive dynamic that drives a market economy with cooperation manifesting itself in the division of labor and competition manifesting itself as the creative destruction of the marketplace. Both forces provide needed efficiencies so that the boundaries of scarcity are progressively pushed back further and further. Each of these forces, in its own way, makes the best use of the available information within an economy so that the highest value utility for a given set of resources can be achieved.

Cooperation is the mechanism that best circulates existing information. It creates the environment in which people can share their experiences and their knowledge on the best ways to use existing resources to make the goods and services we use. The drawback to cooperation is that it doesn’t offer the strong incentives needed to create new knowledge.

In contrast, competition provides the incentives needed for people to discover new knowledge and new methods. It also provides, through the free-market price mechanism, the innumerable messages an economy needs to be able to decide what is working and what is not. Its weakness is that encourages compartmentalization and segregation of knowledge. A healthy economy needs both competition and cooperation working together in proper blend to increase our know-how and to properly share the scarce resources we have.

The Dallas Fed cites two examples of how picking the wrong blend leads to an unbalanced interplay between these two opposing forces.

As a warmup, consider their first example, in which they consider a first come/first served mechanism of sharing resources. A common example of this is the long lines we’ve seen for people to buy the new release of the iPhone. This approach incentivizes people to cooperate by forming a queue in which to wait and to compete by seeing who can get there first and wait the longest. Sadly, both of these outcomes are almost entirely worthless. The competition doesn’t provide any benefit as nothing new is learned or discovered. The cooperation side, beyond providing proof that people can coexist without killing each other, it is also without benefit as the line-waiters have been essentially idle during their wait instead of pursuing so useful (if only to them) activity.

Their second example brings us much closer to understanding the staying power of the above economic warning on cooperation. In this example, the sharing of scarce goods is performed by a government that distributes them. Proponents of government distribution typically justify this method as a way of ensuring that the neediest amongst us get the good and services they deserve. But, as the Dallas Fed correctly identifies, “the rules of government distribution don’t eliminate competition, they just change the type of competition that occurs.” The fact that an identifiable set of people now control how resources are allocated leads to a warped competition in which lobbyists either persuade, cajole, or otherwise incentivize government officials to make outcomes in their favor. What they didn’t identify is that this approach also incentivizes an equally warped form of cooperation.

Under government control, cooperation frequently becomes collusion. For example, it is well known that government regulatory power tends to encourage established firms to spend effort keeping existing regulations in place as a barrier to entry to newer firms. Government entitlement programs tend to habituate the receivers in a multi-generational cycle of dependency. And so on.

In the world of modern scientific exploration, government holds the purse strings for grants and announcements of opportunity. Government officials not only write the terms of these solicitations but also judge the worthiness of every proposal. Much of the judgement exercised in deciding the merits of a proposal comes from the biases and the preconceptions of these officials. As a result, there is a premium placed on ‘exciting new studies’ and ‘concepts that generate buzz’. A researchers end product, typically a portfolio of scientific papers, often becomes a swamp of p-hacking through statistics combined with group think wherein the accepted orthodoxy is reinforced rather than challenged. William Wilson’s article Scientific Regress discusses the serious issues that have arisen under this system wherein an alarmingly large percentage of papers are simply wrong or irreproducible.

The question is then what is it about the system that allows this type of intellectual snake-oil sales to continue? The answer is that the citizens (i.e., scientists) of this microcosmic republic (modern, government-backed, scientific enterprise) have figured out that they can vote themselves money by supporting each other in publishing. Where once there was a healthy balance between competition and cooperation, the trend now is to rely heavily on collusion. You help me get published and I’ll help you and we’ll all benefit directly by seeing our numbers of publications, times cited, impact factor, and so on increase. By colluding, we all stand a better chance to receive government funding.

This self-serving behavior is reinforced by a constant mantra about how important science is and how we need to follow the science and how only the most ignorant of us reject the settled science (a as unscientific concept as there ever could be), etc. The result is that the ‘republic’ of science has heralded it own end. Ben Franklin, our nation’s first premiere scientist must be turning over in his grave.