On Alligators and Elephants

As one travels through the central core of Pennsylvania, winding one’s way along the Susquehanna River valley one finds many interesting attractions. One such attraction is the Little League Baseball International Headquarters nestled in South Williamsport, which hosts the international Little League World Series late each summer. Not more than 10 miles south of Williamsport, overlooking the west branch of the river, is Clyde Peeling’s Reptiland.

Reptiland, featuring many excellent exhibits of poisonous snakes, vibrantly colored poison dart frogs, and ponderous turtles and alligators, is a quaint reptile and amphibian zoo that is fun to visit. However, it was the gift shop that will really catch the eye of someone interested in economics and incentives.

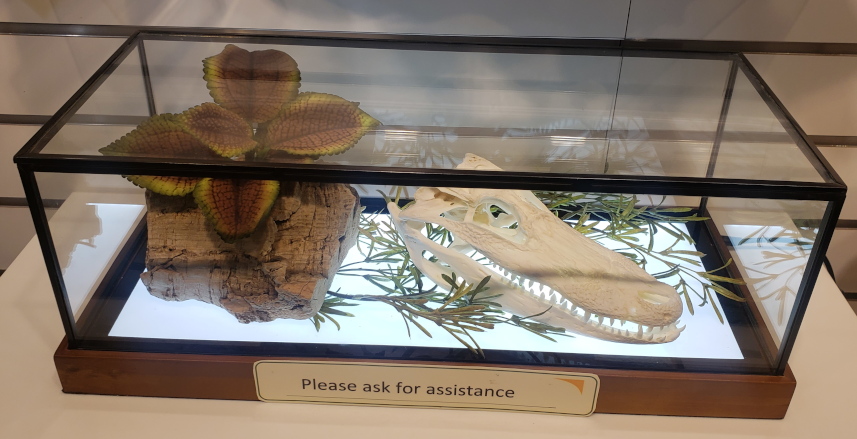

Set upon on of the shelves is a beautiful box containing the bleached skull of an alligator.

Perched above the box, anticipating possible outrage from the economically ignorant, is a sign that explains why the zoo is seemingly betraying its mission.

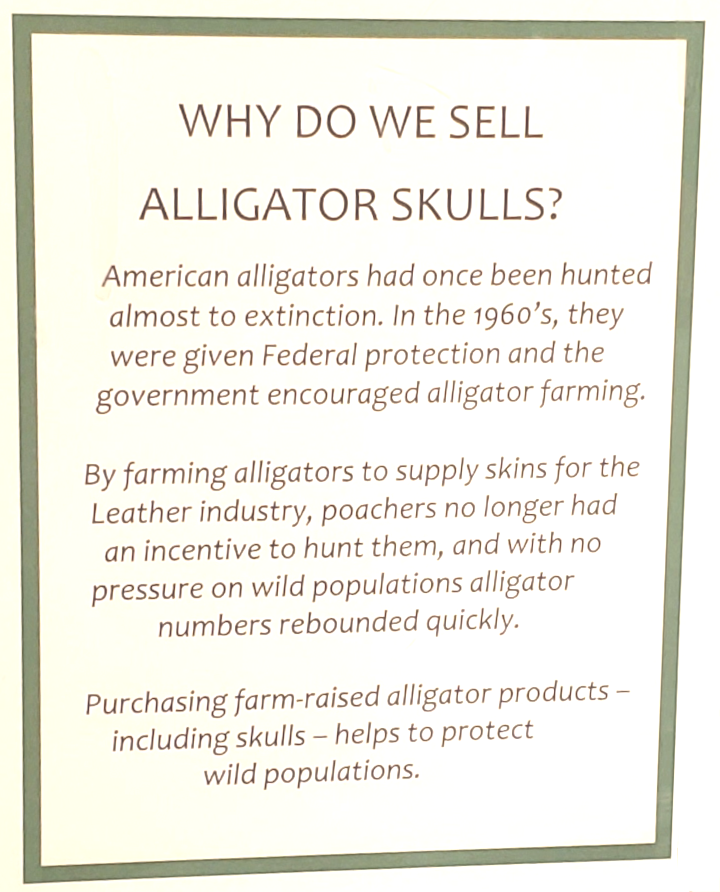

The basic message of the sign is simple: that by allowing people to own alligators we, as a society, are best able to protect alligators. Yes, that ownership comes in the form of farming and farming means that the farmer harvests the animal for parts at the appropriate time. But, intrinsic to the ownership is also the concept of stewardship. The farmer has invested time and capital in raising the ‘herd’ since his livelihood is based on the herd’s health. He will zealously protect that investment in a way that a governmental solution cannot.

Now a careful thinker may object to generalizing this approach to other species. After all, the second paragraph of the sign from Reptiland’s exhibit, which reads

surely, can’t apply to other endangered species such as elephants that are hunted for the ivory in their tusks.

But the public alternative is what we have now. The purchase of real ivory is banned, various governments run ranger programs designed to protect the elephant herds, and still the number of elephants destroyed each year is in the tens of thousands.

Many articles on poaching contain the same litany for the prevention of poaching, litanies that sound good on the surface but fail deeper scrutiny.

As a representative example, Kate Good identifies three broad areas for the average citizen to engage in to stop poaching in her article 10 Simple Ways YOU Can Help Stop Wildlife Poaching Today: 1) sign petitions, 2) provide donations, and 3) volunteer. Although the critiques against them overlap, let’s look at these three in turn by comparing these efforts as applied to the illicit drug trade and arms trafficking, similar types of crime as poaching that Good identifies in her article.

The US has had a vigorous campaign to raise awareness against the use of drugs for decades now with the most recognizable aspects coming in the form of the Just Say No advertising campaign and similar efforts. Nonetheless, the use of illegal drugs has never gone away and, being generous, the best that can be said about the drug prevention efforts are that they have blunted the number of drug users by a small percentage – a valuable effort perhaps. The flaw in the thinking is philosophical. These programs assume that the key to prevention revolves around knowledge; that if the potential user knows drugs are bad then they won’t use them. But this attitude flies in the face of everything we know about human nature. Generally, people know what is right and what is wrong (even if they don’t deeply understand all the implications) and choose to do wrong all the time. The same holds for signing anti-poaching petitions. Which of the current spate of poachers is suddenly going to be enlightened?

Next, let’s look at providing donations. Good’s first suggestion is to “[d]onate through the WWF’s Back a Ranger Project to benefit the men and women who put themselves on the front lines against animal poachers.” Rangers, like police officers, serve an important role in fighting crime but, like conventional police, their primary function is to catch the criminal after the event has taken place. Rarely can any law enforcement officer prevent the crime from occurring, especially in the case of poaching where the victim is unable to speak or call for help and lives on millions of sparsely populated lands. The fact that neither laws nor law enforcers form a significant deterrent can be seen from the fact that some countries even punished poaching by death. If capital punishment doesn’t act as a deterrent to murder which set of new laws is going to make the criminal suddenly decide the risk isn’t worth it? Donations to other entities is even more ineffectual. As discussed above on the critique to signing petitions, which criminal is going to have his heart swayed by a touching video or post that comes across his feed?

Good puts volunteering in the final category. She suggests that the average person can volunteer to help either the indirect efforts (petitioning, messaging, lobbying, etc.) or the direct efforts (patrolling and protecting). The same critiques leveled for the first two categories apply here. No government agency will benefit from volunteers in enforcing weapons trafficking and, I suspect, no ranger in Africa or India will benefit from a well-intentioned amateur.

The solution lies in recognizing, as was done for the alligator problem, that poaching is symptom of the tragedy of the commons, as Adam Magoon argues in his article Elephant Poaching: National Tragedy or Tragedy of the Commons?. The idea is to privatize the ownership of elephant herds in just the way that domestic alligators are farmed. Let someone get rich from a legal ivory trade in perpetuity. That someone will ensure that the herd is well cared for and in no danger of going extinct. That someone will police the lands with vigor and resources unmatched by the government rangers because that someone will have a vested interest in keeping the herd healthy. Some of the details of how to effect this change can be found in Magoon’s article; others can be found in the general economics literature. But the first step comes from recognizing that when government (i.e., all of us) owns a thing, nobody owns that thing and that thing is, therefore, poised for destruction by the tragedy of the commons.