I’m not sure if the academic economists pay attention to the start of football season but they should. I’m also not sure that they play videogames, particularly MMORPG, but they should as well. The reason for these recommendations is not that the practitioners of the dismal science need some fun. I am sure that they do but that’s beside the point. No, my recommendations stem from the fact these both of these pastimes occupy a huge amount of people time and wherever there is people time involved economics is close behind.

Consider, for example, that at the beginning of each football season, there is a wonderful and voluntary establishment of a huge host of microeconomies on a scale nomies roeconomies antion to the a scale undreamt of by Adam Smith or Milton Friedman. Of course I am talking about the establishment hundreds of thousands or, perhaps, millions of fantasy football leagues usually filled with anywhere from 8 to 16 teams, most bearing creative or absurd names.

For those who don’t know, the owner/manager of a fantasy football team selects players from the existing rosters of the 32 teams that comprise the National Football League. The standard recipe is that the points a player earns during a game are credited to the fantasy football owner’s team. In addition, the players also earn their fantasy team points for performance milestones such as 0.1 points for every 10 yards rushing or every 10 yards receiving, although this later advancement was only widely adopted once fantasy football moved from newspaper box scores to the internet (yes, sadly, I am that old and I have been playing fantasy football for over 25 years). To be complete, the concept of player requires some clarification. To simulate the importance of the defense and special teams (punt and kickoff returns), the idea of a ‘player’ is extended to include an entire team’s defensive and kick return units. Point come from touchdowns scored on kick returns and defensive scores (pick six, safeties, etc.) and from performance milestones such as interceptions, fumbles recovered, and points allowed (lower being better).

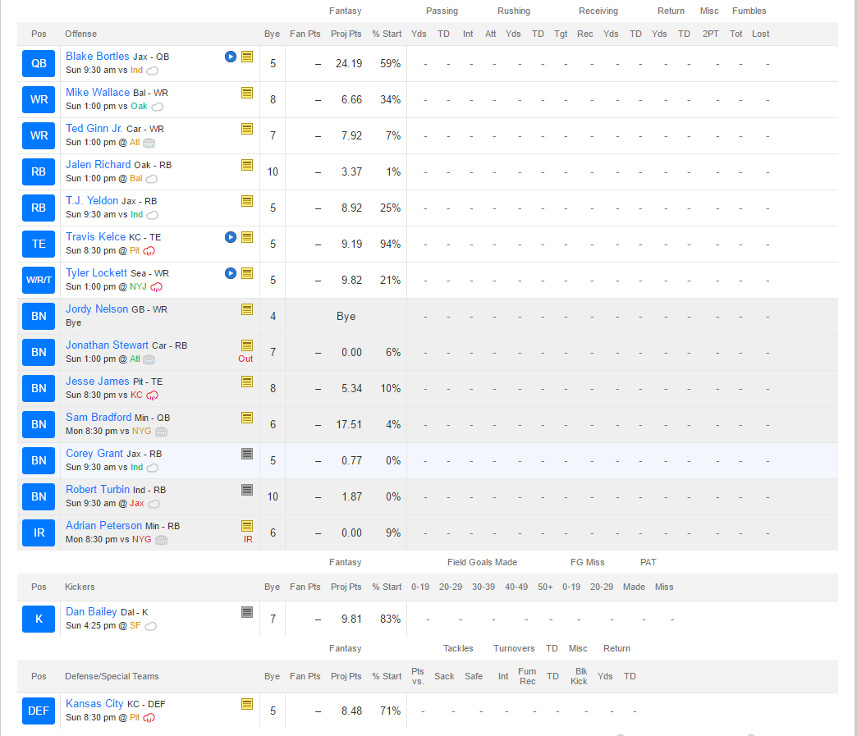

A possible team configuration might be (and unfortunately is)

Team owners draft based on a pre-determined order that usually snakes forward and back every other round so that an owner with a low pick in one round has a high pick in the next round and so on. Players are the exclusive property of the team to which they belong and every owner must fill out a roster that has representation in the key skill areas: quarterback, running back, wide receiver, tight end, place kicker, and defense/special teams.

And so we arrive at the first set of the many economic lessons provided by fantasy football: the ideas of scarcity, constraints, and substitution. As the number of teams in a league increases the ability of each team to have more than one or two exceptional players decreases. Owners are forced to fill in required positions with players that aren’t top of the line. There is simply no way to stack a team with only quarterbacks or placekickers (generally the two highest scoring positions). In addition, owners must find credible backups to handle the bye weeks where some teams don’t play and to mitigate the possibility of a serious or even season-ending injury (yes Adrian Peterson and Danny Woodhead I am lamenting your loss).

The next lesson centers on the concept of comparative advantage. The different skill positions have very different drop offs in terms of points. The top of the line quarterbacks (e.g. Tom Brady or Drew Brees) may earn 25 points/week but the drop in points is such that the 16th quarterback may earn only 30% fewer points (18 points/week). The top running backs may only earn 19 points/week but the drop is steeper at nearly 37% fewer points (12 points/week). Since an owner must field two running backs and good running backs are harder to find, there is a comparative advantage to taking running backs before quarterbacks, even though the quarterback position scores more points. If an owner gets two top-flight running backs and one mid-tier quarterback he stands to earn 56 points/week compared with 49 points/week with a star quarterback and mid-tier running backs. Taking into account the relative scarcity of running backs, makes the analysis swing more heavily towards drafting them above passers.

Another very useful lesson driven home by fantasy football is the notion of opportunity cost. Generally, it will turn out that an owner will have a glut of good players in one position, say receiver, and a dearth in another, say running back (again my heart aches over Adrian Peterson) or quarterback. The smart owner will no doubt wish to trade from his surplus to fill his lack. Sometimes this will result in what, on the surface, looks like an inequitable trade. Issac M. Morehouse details in a fun and very readable post a story of how a trade that was beneficial to him was vetoed by the commissioner of his league because the later judge it to be unfair. Morehouse was willing to give a 25 point/week-player from his roster in exchange for a 15 point/week-player in order to fill a gap. The fact that the point total seemed lopsided (giving up 25 points/week for 15 points/week) didn’t take into account the opportunity cost that Morehouse would suffer by not being able to field an entire roster.

Okay, I’ve obviously made a case for fantasy football being a tool to teach economics but what can academic economists – the guys who teach this stuff at the university level – hope to learn? Well, the short answer is that all of these fantasy football leagues are as close to an ensemble of repeatable experiments as economists are ever likely to get. Each league of similar type is one trial in a huge self-organizing experiment where the participants want to win and strive against each other and the economic realities to do so. The fact that the size of a given league is small is offset by the great number of copies that exist. I don’t know if professional economists are studying fantasy football but I do know that it has been bandied about.

And if sports isn’t their thing there are tons of choices from the realm of videogames. In particular MMORPGs, which typically have high incentives built in that reward time played with levels, achievements, and the like, are especially attractive. And since the players are in the real world, even if their imaginations are in cyberspace, and they spend real time (and sometimes real money) commodities in the virtual space often become real commodities.

During the Warcraft craze 5-10 years back, one could but high level characters on eBay. Specialized merchants cropped up who offered to either deliver a high-level character directly to the customer or take a customer’s existing character and level it up. These services were exchanged for payment in real-world dollars, which reflected the time and skill of the leveler.

Even the so-called casual gamer can engage in virtual economies of differing complexities. Members of my own family are partial to Neopets and the various mixes of capitalism and socialism that can be found within that universe.

Regardless of the form a pastime takes or the venue in which it is embodied, real time is spent by real people, who, maybe without even knowing it, are forming lots of microeconomies that can teach us all some big lessons.