Robbing Peter to Pay Paul

There is a curious thing about the Eurozone that doesn’t get much notice but it really should. On the surface, the Eurozone seems to be a similar economic model to the United States, but the lack of a common culture and free movement within the member countries results in barriers that can actually cause wealth transfer from poorer members to richer ones.

In the US, an individual can move freely between the states (although setting up residency is a bit harder). Interstate purchases are open and easy, especially in the age of the internet. Workers can move from states with declining economic prospects to those with an uptrend, resulting in the kind of demographic shifts such as the recent influx into Nebraska and Texas and corresponding exodus from California and New York. In other words, things have a way of evening out since the barriers for trade between the states are very low (but not nonexistent – consider that many decisions made in California set standards across the other 49 states). Very few products made in the US are distinctly branded by the state in which they were produced. Most of us are aware that there are Florida Oranges and Idaho Potatoes but beyond that few of us know where a good is produced.

Take automobiles. Once it was obvious which cars were produced in Detroit but now few people actually know, or care, in which state is located the manufacturing plant that birthed their car. Likewise, few of us are conscious where most of the things we purchase originate.

The Eurozone, in contrast, is much more rigid. The euro is the shared currency throughout the Eurozone but the mechanics of inter-zone trade works quite differently from the US experience with the dollar. The major difference is that in the Eurozone goods, services and labor from one country are produced essentially independently from the other countries. When one is in Germany, say in the city of Munich, one is clearly aware what products are imports (mostly clothes) and what products are German in origin (most everything else). This is especially true in the realm of cars. It makes no sense to talk about Pennsylvania cars as distinguished from Montana cars but it is quite natural to talk about German cars as compared to those from France, Sweden, or Italy. In addition, French workers can’t just pick up and head for Germany any more than they could to Japan. There are barriers – political, cultural (language in particular), legal, and bureaucratic – that really impede that kind of movement.

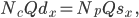

To see how these barriers provide a mechanism for wealth transfer, start with a simple model of international trade limited to just two countries. Let country G stand for Germany and U for the United States. Both countries have their own currency (gold coin denoted as D for G and greenbacks and silver denoted as U for U) and the exchange rate between the two is shown in the yellow box. Time progresses from left to right.

Now suppose the good that is being traded is cars; G has cars it wants to sell to people in U. At the initial time, the exchange rate favors G, as its currency is undervalued compared to U, and G promptly ships some number of cars to U. Upon arrival in U, the cars make their way to a dealership where a citizen of U, call him C, purchases one. C pays for the car with U currency and happily drives away completely unconcerned with how the money makes its way back to G; that isn’t C’s problem. G’s agents in the U have to deal with that. They do so by finding someone willing to buy Us for Ds. Since the supply of Ds in the exchange market goes up, there is a upward pressure on the value of Us compared to Ds and soon the exchange rate reflects that by adjusting the buying power of G, compared with U, down to parity. This floating currency exchange serves to naturally limit the number of cars that G can sell in U and an equilibrium results.

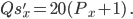

Next, expand the model so that G is part of a larger economic entity comprised of itself and H (H stand here for Greece – either because H comes after G or because Hellenic is an adjective used for ancient Greece; the reader is free to decide for himself). Also suppose the H has no goods to trade with U at all.

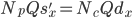

Now suppose the same situation occurs in this new model as occurred in the old. G has cars to sell and U has people wanting to purchase them. H is a complete bystander in the first leg of the transaction, having no goods to ship to U. However, H plays a pivotal role when the currency exchange occurs after the purchase. Since there is a larger supply of U, as H has a supply in addition to G, there is less of a mismatch on the exchange market and less of an upward pressure on D (or downward on U). Simply put there are now fewer Ds chasing Us in a relative sense. It takes longer for an equilibrium to set and during this time, H’s purchasing power is remains low.

So although there is no direct exchange of either currency or products between them, H effectively transfers wealth to G in the form of better export conditions for G and poorer import conditions for H. The poorer H is, the more pronounced is the drag it produces on the upward trend in D, the longer it takes to reach equilibrium and the more wealth is transferred. If people could move freely between H and G, then a mechanism would exist to equilibrate faster and more citizens of H would share in G’s windfall. In some real sense, it's like U is robbing H to pay G.

Although these models are highly simplified, they reasonably capture the essence of some of the tricky situations that result with import/exports and currency exchanges. Several interesting articles exist (a nice one can be found here) on similar situations during the Nixon presidency that ushered in the end of the Bretton Woods System. But that is a story for another day.