Money and Inflation

By all measures, June is the ‘summer’ month. By popular rendering, June is the first month of summer following hard on the heels of the common entry into that season with the passing of Memorial Day. By official rendering, June is also the official, astronomical start of the summer given that it contains the summer solstice when the day is as long as long can be. And, by all measures, Americans are going to be paying more for their summer fun especially if that fun centers around food or driving anywhere or doing anything. About the only thing that is cheap right now is talk so we’ll expend some of that tracing the roots of the current price hikes we all see.

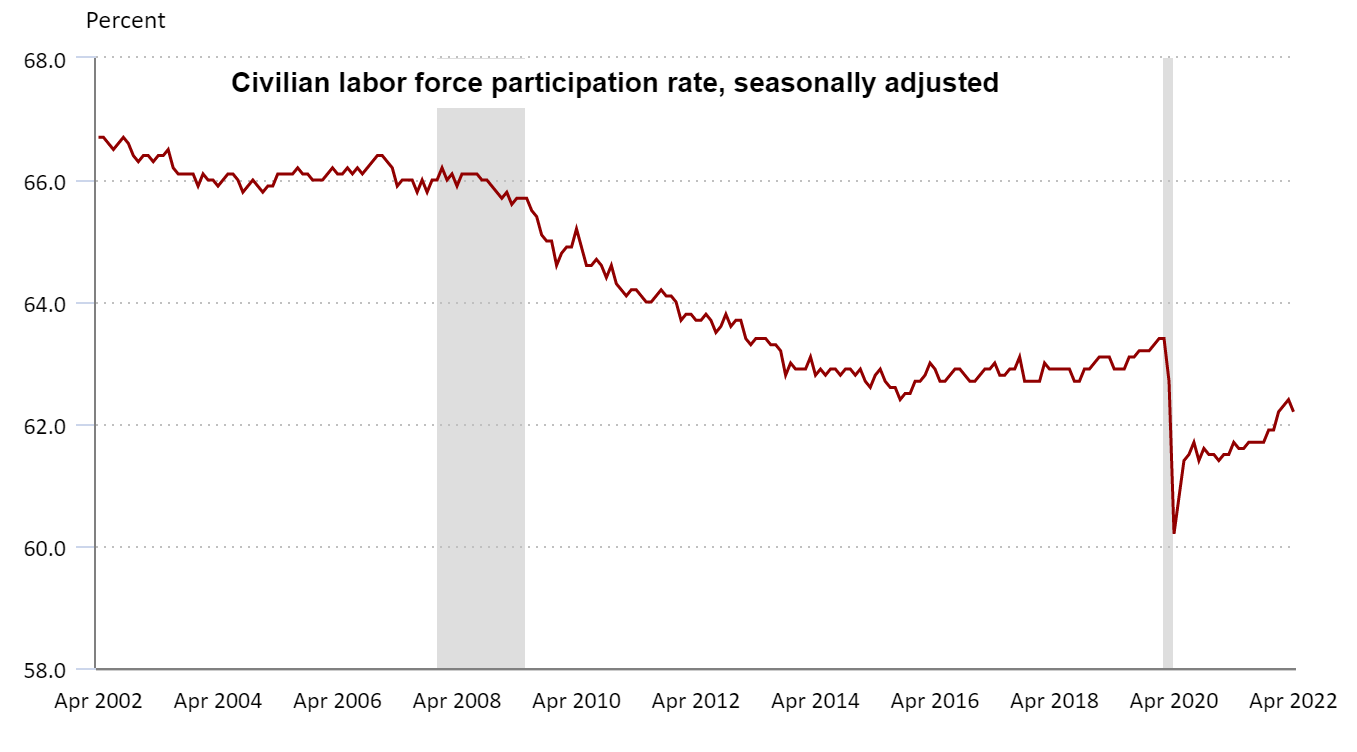

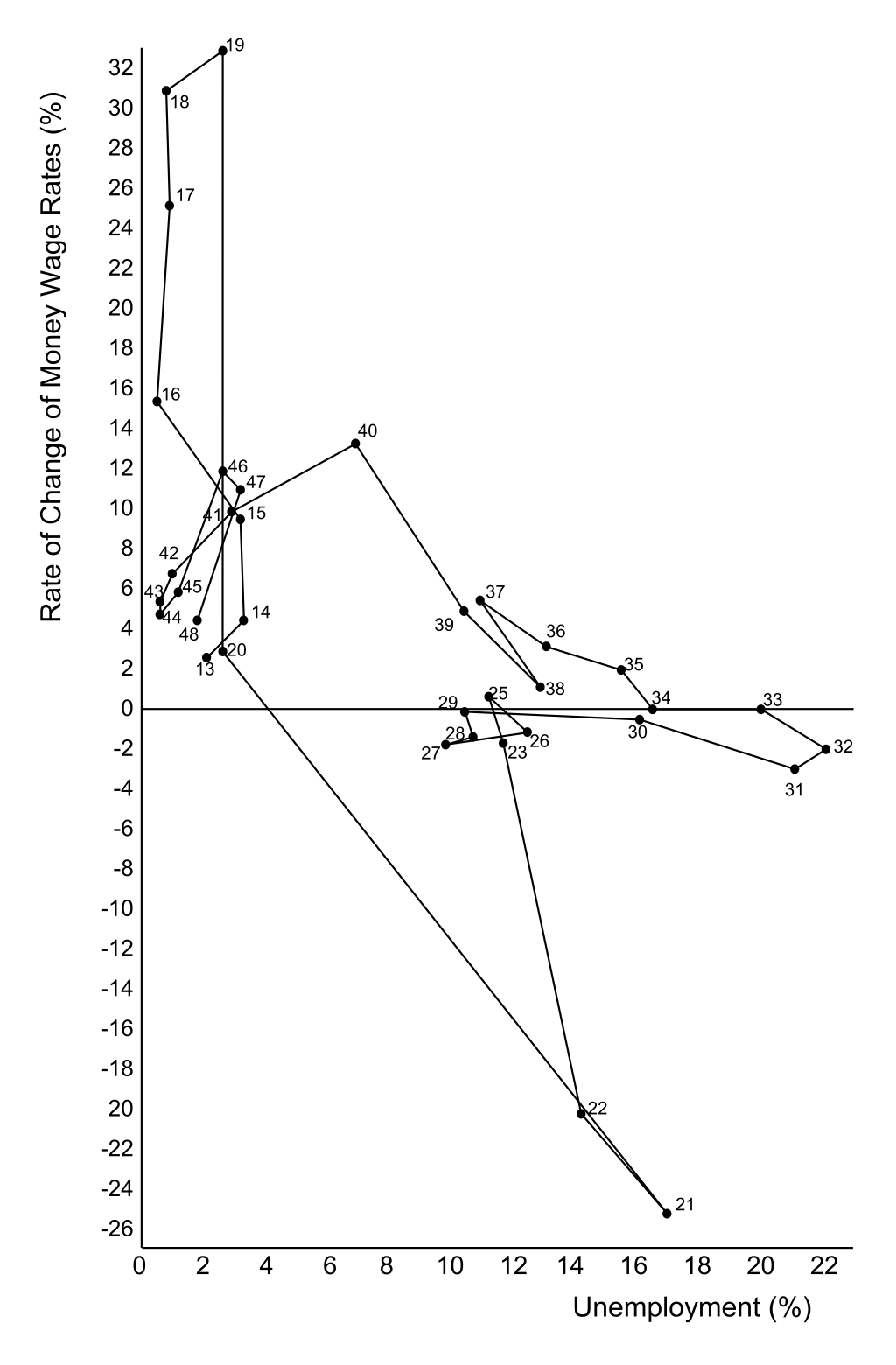

System inflation was already rearing its ugly head back in September 2021 and at that time this column discussed the very real possibility that what was labeled as ‘transitory’ might be here for some time in post entitled Stagflation and the Phillips Curve. Sadly, here it is nearly a year later and inflation has nestled into the American economic land scape for the long haul. The question is why?

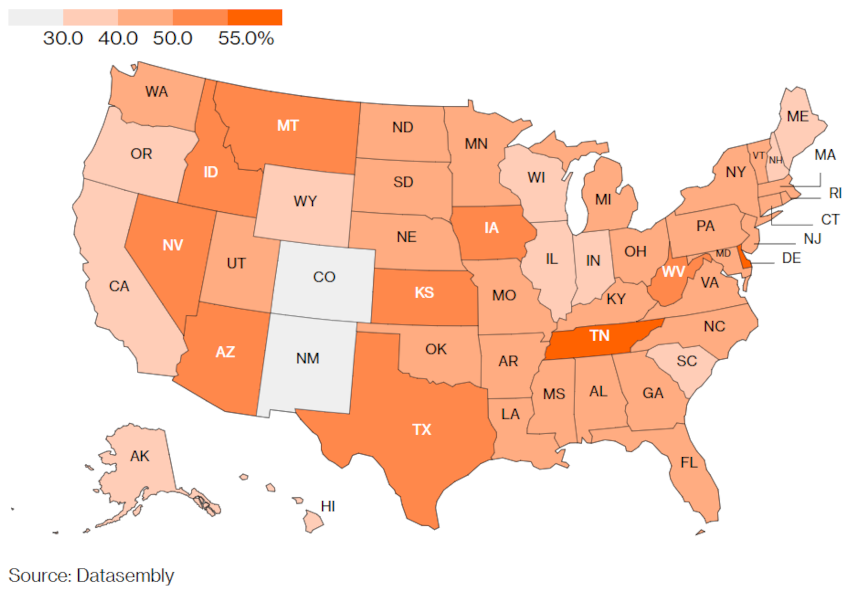

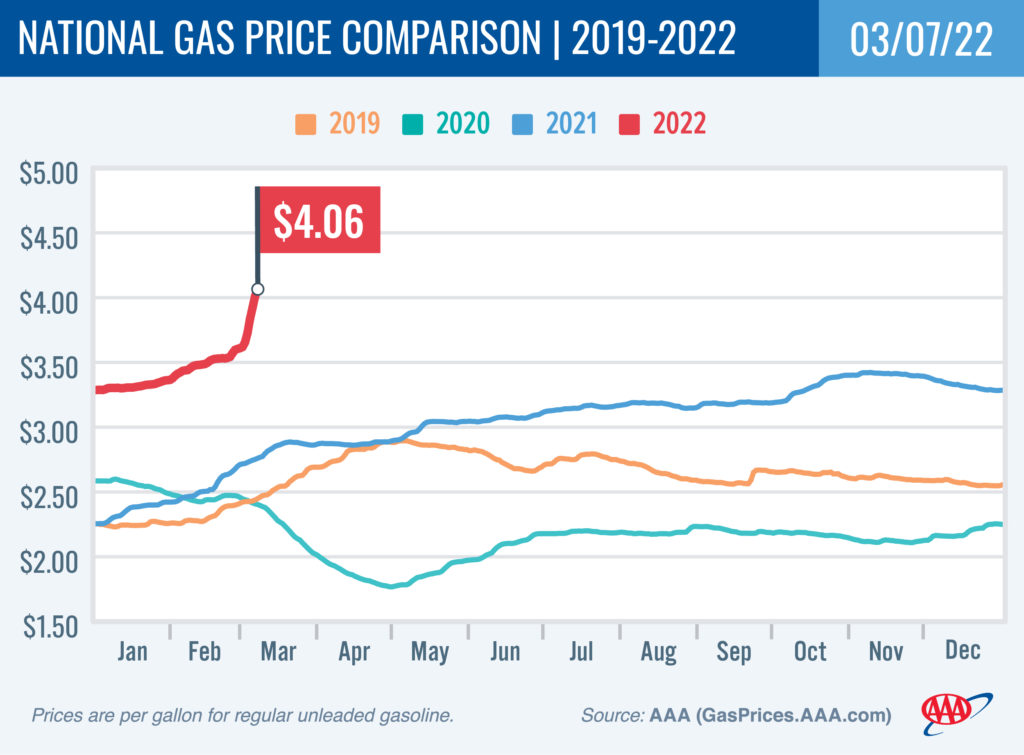

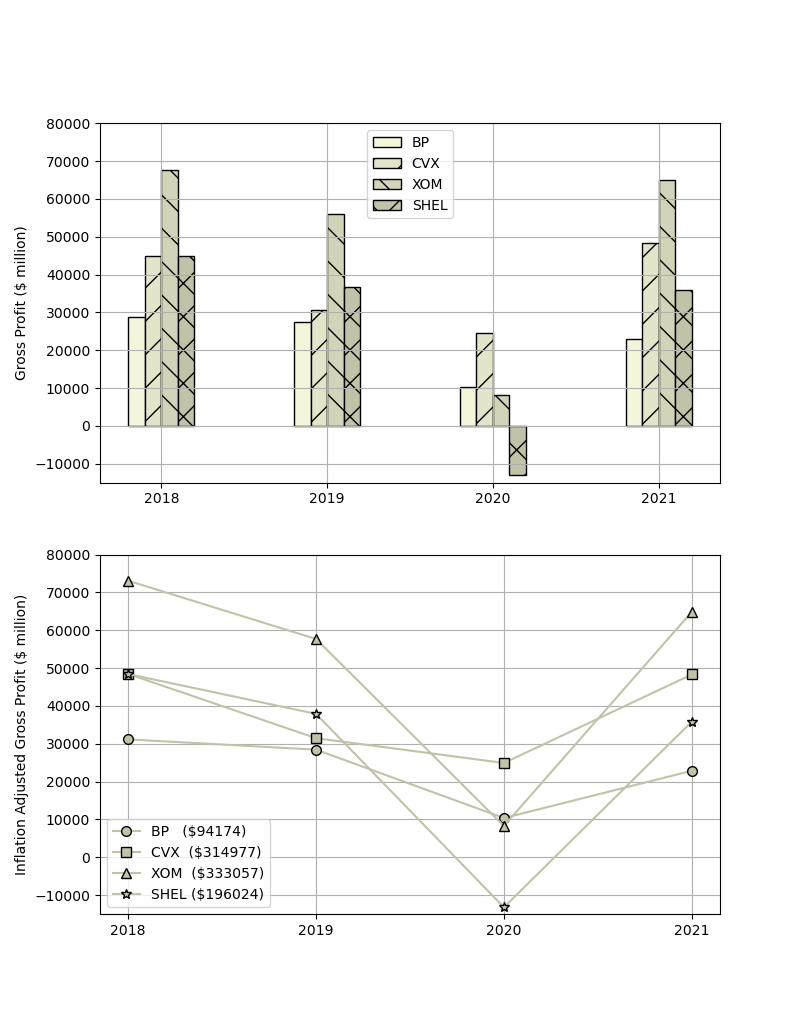

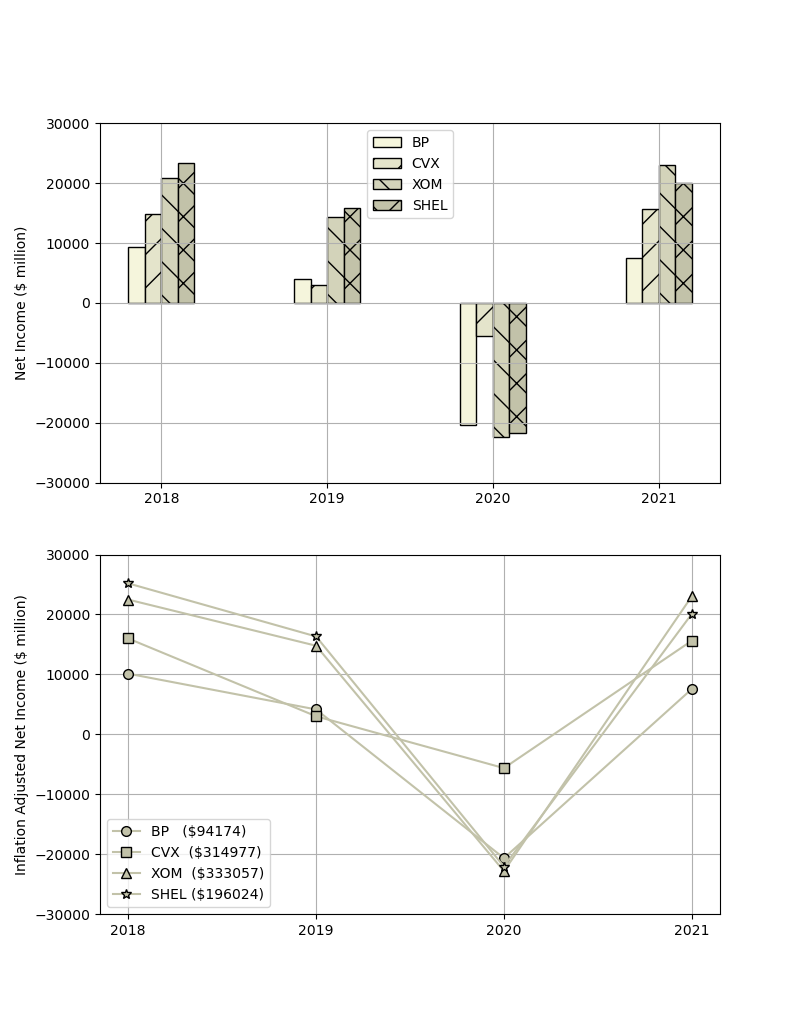

Contrary to some popular opinions, the core answer is not to be found in gasoline prices – they are merely a symptom. Localized shortages, likes those experienced with the Colonial Pipeline shutdown, can drive prices up for a period of time but they can’t effect every sector in the economy. But we don’t have shortages of gasoline, we have a systemic rise in the price of gas nationwide that is not due to ‘the rapacious greed’ of oil companies. And, given that the price of gasoline figures into the cost of most everything else, higher transportation costs do get passed onto the consumer and so rising gas prices do have a compounding effect, even if they are not the root cause.

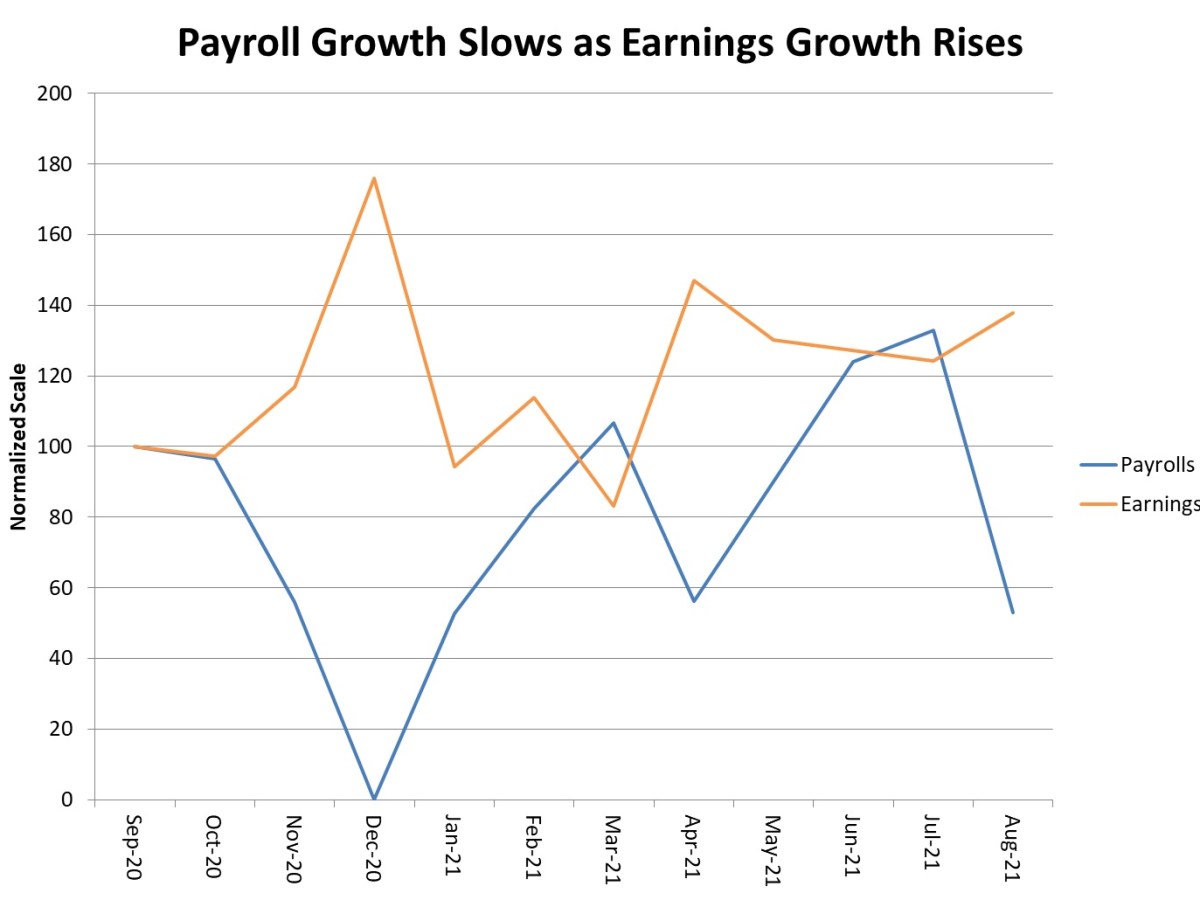

The other popular answer that inflation is a direct result of government spending hits closer to the mark but doesn’t quite get there either. Fox Business showed a graphic very similar to the one shown below marking the steps of inflation over the last 15 months in attempt to indict the Biden administration’s ‘reckless spending’ as the culprit of high inflation.

The graphic is compelling (even though the box layout and connecting lines are bit confusing) but spending, in and of itself, cannot be the source of economy-wide inflation.

Excellent examples of counter-arguments are found each and every Christmas when some fad takes root and the latest ‘hot toy’ emerges. To be concrete, no one could have foreseen the intense demand that the Nintendo Wii would command when it came out during the fall of 2006. Each Wii became such a hot commodity that stores sold out and large resell market developed. People who had the financial wherewithal to spend small fortunes threw cash around, thereby driving the price up in advance of Christmas day. And yet, the economy as a whole didn’t suffer inflation. Other, more modern, examples of ‘runaway prices’ include the Game Stop stock bump and the Dr. Seuss scare where prices of those commodities rose sharply but, nonetheless, did not trigger economy-wide inflation.

With that in hand, let’s return to the Fox Business argument and unpack it a bit. If the graphic they provided seems to prove that government spending if the culprit but, as was just argued, spending itself can’t be to blame, how can we square these two different points? The reconciliation lies in not what amount government spent or in what sectors of the economy that spending occurred but rather in how government acquired the money it spent.

When a given individual, household, or firm spends it either takes from its savings or it borrows from someone else’s in order to pay for what it wants or needs. Government has a third option: it can simply print more money. In exercising this third option, government typically triggers systemic, economy-wide inflation. The following excerpt from a talk given Milton Friedman drives this point home.

During the course of the 15 months covered by the graphic above, the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply from approximately $15.5 trillion to $21.6 trillion, an increase of just about 40%. In the article entitled, Inflation has Fed critics pointing to spike in money supply, author David J. Lynch does a nice job in making Friedman’s case that inflation is monetary in origin.

To be fair, Lynch also covers the counter-argument that the Fed is currently mounting by noting that:

That’s one reason that the Fed’s money creation isn’t driving inflation, according to many economists. Yes, there is a great deal more money stored in various forms. But it is moving through the economy more slowly than at almost any time in 65 years.

But this ‘velocity-of-money’ justification for severing the link between money supply and inflation seems hard to reconcile with the Fed now pushing to raise the prime rate. Making money harder to borrow will result in an even lower velocity. In addition, according to the article Small US Companies Lose Almost 300,000 Jobs Since February by Alex Tansi of yahoo!finance, there is likely a significant cost to small business growth with this approach:

So why not just contract the money supply? There are several reasons. First and the most important one is that such a course of action almost invariably triggers a recession. Second, it isn’t at all clear that all types of money are equal. Cash stuffed under the mattress is technically in the supply but is doing nothing to stimulate economic activity. So, how much should the Fed cut and where? These questions make it hard to find a precise procedure for taming inflation but it seems clear that statements like the one Lynch cites from Fed Chair Jerome H. Powell that assert that

should be taken with a large grain of salt. These statements sound a lot like the expert assertions from the early 2000s that said we were in a new economy in years leading up to the Great Recession of 2008.

Sadly, this is where the story stops. It looks like we’re going to have to live with inflation for the foreseeable future and it looks like the ‘economists in the know’ are anything but knowledgeable. My own money is on the monetary-supply theory precisely because it following Occam’s razor and it jibes with what we know are fundamental features of the economy.