March Banking Madness – Part 2, What to do Now

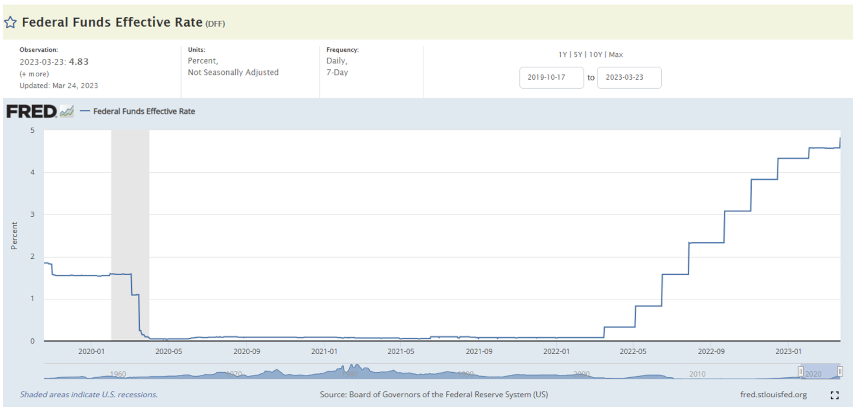

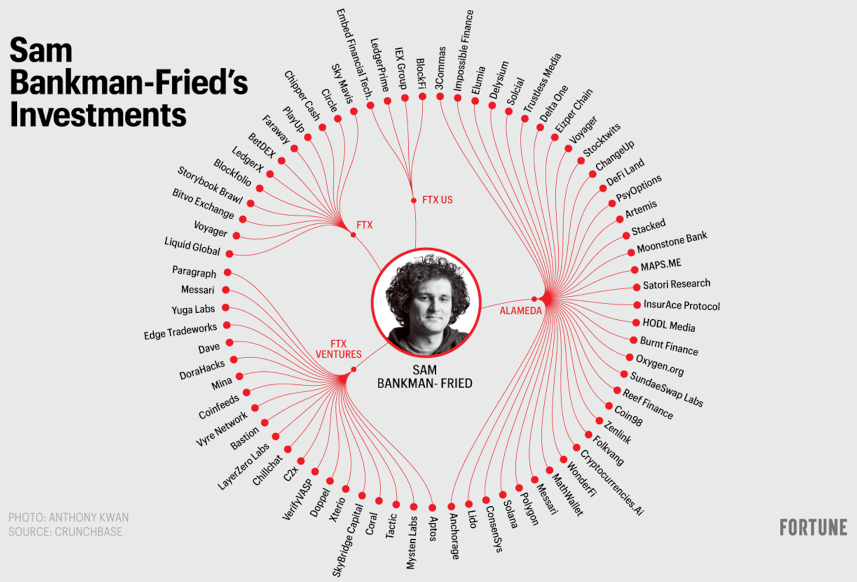

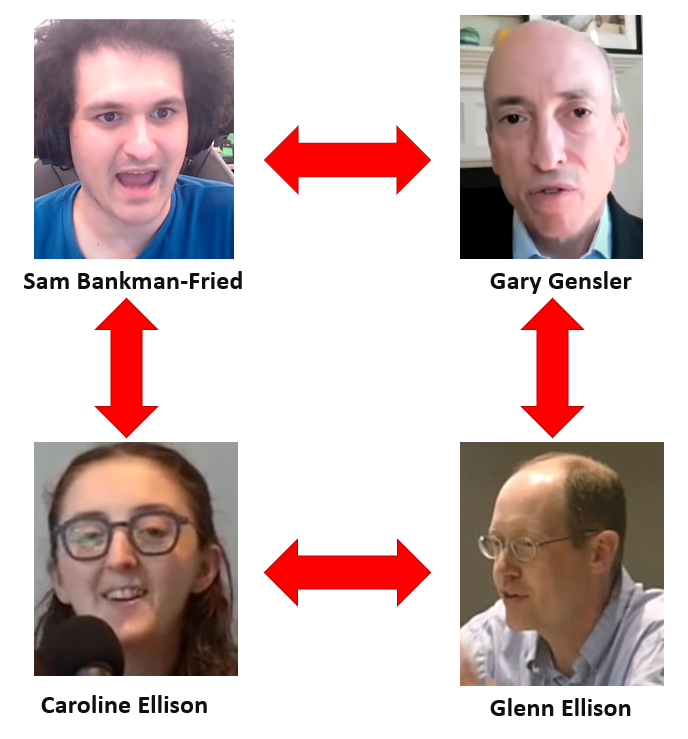

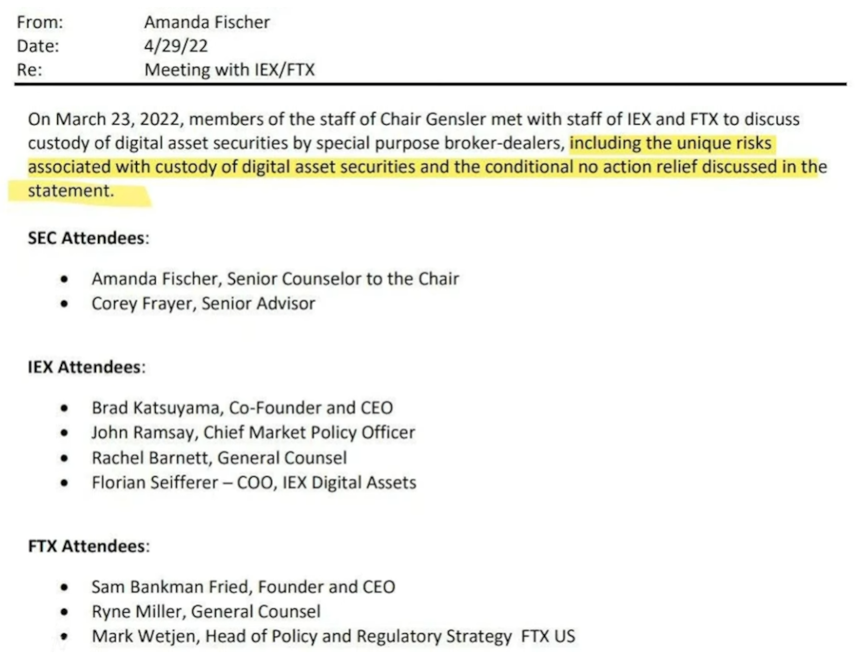

Last month’s post looked at the causes of the various bank failures that dominated the March news cycles well-beyond the financial circles and which penetrated general news cycles and everyday discussions held at work and over the dinner table. The reasons for these failures were a combination of exposure to the weakness to cryptocurrencies in the wake of the FTX failure coupled with inadequate hedges against rising interest rates. In the case of Silvergate, that bank voluntarily began liquidation in advance of shuttering and the size of the overall assets that were affected is rather small. In the case of Credit Suisse, an agreement was reached with UBS to save the bank though the latter’s purchase. However, two of these banks, namely Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, were liquidated and sent into receivership making them two of the largest bank failures in US history. The following table, adapted from Wikipedia’s list of the largest banking failures in the US, shows that they occupy the second and third place on the all-time list, when adjusted for inflation.

| Bank | State | Year | Assets at time of failure ($B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Inflation-adjusted (2021) | |||

| Washington Mutual | Washington | 2008 | $307 | $386 |

| Silicon Valley Bank | California | 2023 | $209 | $209 |

| Signature Bank | New York | 2023 | $118 | $118 |

| Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust | Illinois | 1984 | $40.0 | $104 |

| First Republic Bank Corporation | Texas | 1988 | $32.5 | $74 |

| American Savings and Loan | California | 1988 | $30.2 | $69 |

| Bank of New England | Massachusetts | 1991 | $21.7 | $43 |

| IndyMac | California | 2008 | $32.0 | $40 |

| MCorp | Texas | 1989 | $18.5 | $40 |

| Gibraltar Savings and Loan | California | 1989 | $15.1 | $33 |

Okay, these failures were big. In fact, SVB and Signature bank failures come in at the second and third on the list and, in combination, are almost as large as the holder of first place. So, the next point is obviously what should be done about these.

Ordinarily, in the event a bank fails, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) will step in a restore depositors up to a ceiling amount of $250,000 dollars per account. But in the case of SVB, reports state that over 90% of its depositors were well over that mark, most of the accounts being associated with business to meet payroll. However, the US Treasury Department, the FDIC and the Federal Reserve, announced in a joint statement that depositors in both banks would be made whole. Supposedly, this restoration will be done without no cost being passed on from the financial sector according to the article U.S. government steps in to shore up deposits at Silicon Valley Bank and another failed institution by CBS News:

but it is very difficult to see how this can be true. Even if the costs are not passed directly onto bank consumers, the financial institutions that supply the funds will cut back in other areas. To quote an old adage: there is no such thing as a free lunch.

Included in the arguments for making the depositors at these banks whole are the facts that: failures of this size pose a systemic risk to the economy; the depositors, being primarily businesses, need to have large sums of liquidity available for payroll, and so can’t reasonably have accounts below the FDIC maximum; that the depositors weren’t responsible for the bank mismanagement, and so on.

I am certainly sympathetic to the arguments concerning the depositors and I am willing to agree that they had no knowledge or culpability in the mismanagement of these institutions and that the $250,000 ceiling, while perhaps viable for a household account, is entirely inadequate for a business. But I am deeply opposed to the systemic risk argument.

That type of argument is simply another way of repackaging ‘To Big To Fail’. A host of moral hazards follow in its train. The first, and maybe most obvious, moral hazard is that making depositors whole lowers the incentive that they, and others like them, will call for societal change in how banks are run. To give an example of how this lack of incentive might work, consider the fact that for the last 8 months of its existence SVB went without a risk manager and that the regulators knew that. If each of the clients are made whole there will be no outcry, no demands, no lawsuits, etc. It will be just a quiet return to the status quo with no outrage fuel calls for change that might actually work. Future institutions will be given an implicit green light for more risky chicanery while government regulators will be excused from their inaction and invited to being even more hands off.

The second, less obvious but more important moral hazard is that bailing out the depositors provides a set of perverse incentives concerning their behavior. Bank customers will again be lulled into being ill-informed about the financial institutions that they trust, picking a bank based more on getting a free toaster than on the soundness of the institution (full confession – I never thought about investigating the soundness of a bank until now). But far more concerning is that this ‘bailout’ now provides a strong incentive for depositors to gravitate to the big banks (e.g., Bank of America, Chase, Wells Fargo, Citi, etc.) thinking that there is an implicit governmental promise of being made whole. This is the very point that Senator Lankford makes in his question of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

As depositors being to get that message that ‘To Big To Fail’ benefits them as much as it does the financial firms and regulators, choices in banking will dimmish. Community banks will begin to disappear and, with what is essentially a regulatory imprimatur, the larger institutions will have no incentives to manage risk. Eventually, there won’t be enough bailout funds and the entire system will collapse. That is the argument against making the depositors whole.