A curious situation came to light over the Thanksgiving holiday this year that offers a microcosm in which to examine the role of government regulation on the free market.

The New York Times, in their Upshot column, published an article entitled ‘Taxi Owners In New York Seek Inquiry on Medallion Prices’ by Josh Barro. In this article, Mr. Barro reports about a beef that the taxi drivers of New York have with the governmental body that regulates them.

On one side is The Greater New York Taxi Association (GYNTA), which represents the taxi industry. One the other side is the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC) representing the city government. At the center of the dispute is a report that TLC published on the average price for taxi medallions. A taxi medallion is a license that allows its owner to legally operate a yellow taxi within the city limits (from TLC website)

A taxicab medallion is not only a valuable asset, it is also a license from the Taxi and Limousine Commission to operate a New York City taxicab.

TLC regulates the number of medallions that are active in the market, and sets the initial purchase price when new ones become available. All other transactions occur between businesses, who either buy or sell – much like the exchange of securities on the stock market – based on need. As the TLC states clearly on the their website

Any change in the ownership of a taxicab medallion must be approved by the TLC, and any new owner must apply and be approved for licensure before assuming an ownership interest in a medallion.

In addition, they track them and record the price as part of their regulatory function, and make the statistics associated with these transactions a matter of public record.

According to Mr. Barro’s article, TLC’s report has listed the price for medallions as holding steady at or near the peak they reached in the spring of 2013 when, during that same period, ‘they were actually falling’. Depending on the type of medallion being purchased, the price drops range from 17 to 25 percent. As further evidence that something is not quite correct, Barro states:

However, in eight months in 2013 and 2014, the commission [TLC] reported averages that exceeded all actual prices for individual medallions. For example, the commission’s report for February 2014 reflected 14 transfers of individual medallions for an average of $1.05 million. In fact, there were 15 transfers, none at a price higher than $1 million.

The original report has since been pulled from the TLC website, so an independent scrub of the data and the conclusions is not possible. But in an earlier article, Barro attributes the competition from Uber and Lyft as the source for the downward pressure on the medallion prices, which had peaked at over $1,000,000 per medallion, and are now slightly above $870,000. In addition, he provides this additional nugget on how the TLC generates its statistics:

In fact, individual medallions have traded below $1 million for most of the last year. But the commission excludes from its statistics any transaction at a price more than $10,000 below the previous month’s reported average.

The rule just listed should disturb anyone with even a rudimentary exposure to statistics. With a peak asking price at a million dollars, a $10K fluctuation in price is approximately one percent. To put their statistical approach in more familiar terms, consider what would happen if they were charged with tracking the price of a gallon of gasoline. The TLC would say that any price drops that were greater than 3 cents ($0.03) would be ignored.

Is there a way to try to understand why the commission does its statistics in this fashion? To answer this, I started by making a simple survey of the data available on medallion transfers for the calendar year 2014 (Jan-Nov).

During that time span, the TLC lists 69 transfers of individual medallions along with a brief explanatory note on some of them, ostensibly to explain ‘out of family’ prices. It is accepted practice when statistically analyzing a population to exclude outliers, and in certain months this seems to be needed.

For example, the May 2014 record lists 10 transactions, with 7 of them at approximately $1000K, 1 at $880K and 2 others well below those values. One of these two was a medallion sale for $525K with an explanatory note of “Partnership Split” and the other, which sold for just under $81K, bore the note “Selling 10%”.

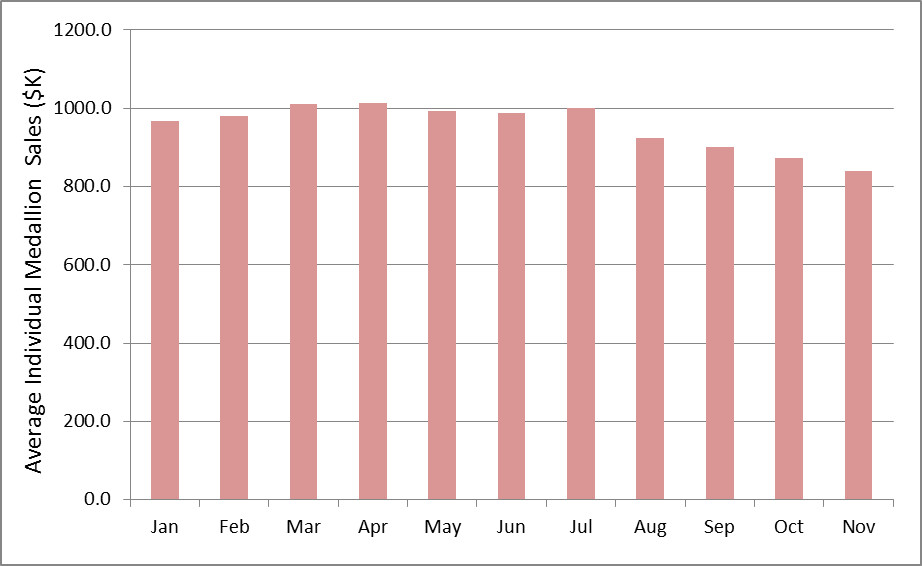

It is reasonable, when trying to appraise the fair market value of the asset, to exclude such outliers where the transaction may have been associated with a desperate situation which may have skewed the asking price from fair market (e.g., an asset had to be liquidated quickly in a “Partnership Split”). Based on this philosophy, I removed from the data all cases where the transaction price was well out of family. This left 62 sales distributed unevenly over the 11 months. The monthly average is shown in the figure following, where a definite downward trend can be seen in the last 4 or 5 months reported (it is important to note that September has only one transaction).

I also tried to characterize the fluctuations in these data, and I used the population standard deviation of the 62 cases as a measure, which gave a reasonable estimation of approximately the price fluctuations at $55K. This number is well over 5 times larger than the $10K used by the commission, and so it is easy to see how their rule of excluding from consideration any transaction that was $10K below the previous month’s average basically led to the conclusion that prices were flat. In effect, the commission’s asymmetric approach introduces a bias into their analysis that simply ignores the statistical data from August to November.

Why might the TLC indulge in such statistical black magic? Well, obviously to protect their own interests; but what exactly are these? Let’s explore some of the possibilities.

The commission is seeking to protect the livelihood of the taxi driver. This seems an unlikely explanation, as propping up the price of a medallion clearly helps the owner maintain his investment while only indirectly helping the driver to maintain his job. The median salary for a taxi driver in New York is about $38K, which is a far cry from having the capital needed to buy a medallion, so it is unlikely that there is a high percentage of owners/drivers in the market.

The TLC is trying to maintain the regulated market in the face of the intrusion by Uber and Lyft. There is a segment of the population who believe that preventing Uber and Lyft entry to the marker would have two benefits. The first is that it would prevent the kind of fare-wars that erode driver pay and would protect their salaries. The second is that Uber and Lyft are not as committed to passenger safety as they should be. Both of these explanations also seem to be unlikely. Uber and Lyft have made huge inroads into the driver-for-hire markets in many US cities with the tacit or explicit permission of the local governance, and so the TLC would be going rogue. Second, there is no evidence that Uber or Lyft drivers commit felonies at any higher rate than yellow cab drivers. In this hyper-connected world, bristling with social media, it is actually in the best interest of Uber and Lyft to have trustworthy drivers. Also, some conventional taxi drivers must be law breakers. else why have a court ruling upholding the commission’s authority to suspend licenses of drivers who break the law.

The TLC is trying to maintain its own influence and position. This is the likeliest explanation. Government bureaucracies trade in their own form of wealth and capital, which is measured by the authority they wield and the favors that they curry from the industries they regulate. GNYTA’s website suggests that their relationship with the TLC is a cozy one when they state

GNYTA was formed because its members shared a vision – a vision of a strong vibrant progressive taxi industry in New York that would partner with government to create the most dynamic, fuel efficient and accessible taxi industry in the world.

GNYTA’s goal is not to be an obstacle but an actual partner with the legitimate goals of government.

Of course it is in GNYTA’s interest to align itself with its regulators as long as the latter controls the number of medallions, thereby maintaining a barrier to entry for competition. It is a classic protectionism arrangement where government and big business are partners for each other’s benefit, and the consumer is of secondary interest. This type of arrangement is sustainable only until an external force upsets the status quo. This is what seems to be happening with the rapid rise of Uber and Lyft, and the cracks in the relationship between the TLC and GNYTA are starting to appear.