Two recent experiences, profoundly annoying and time-consuming ones at that, have driven home the basic economic idea that we should all learn to share a bit more and temper our desire to always reap the greatest benefit without thought to the negative externalities that we may be visiting on others.

The first experiences should be very familiar to cellphone owners in the United States: the relatively recent and sharp rise in the number of telemarketing cold calls that we receive on a weekly basis. Barely a day goes by that I don’t get a call from some unknown number that my caller id identifies as originating from Massachusetts or Michigan or wherever. Often the call comes in during the work day when I am in a meeting or otherwise importantly occupied.

If answered (yes, occasionally, I stupidly decide to listen to what the interloper on the other end wants to say – it’s a weakness), the call inevitably is from someone who is trying to sell me something I don’t want for more money than I can afford to spend. I’ve never summoned enough patience to ask how the telemarketing drone, whose robotic software has graciously selected me from amongst hundreds of millions of possible cellphone numbers, feels about disrupting my day. Nonetheless, I am fairly certain just how the conversation will go.

Drone: Hey! I’m just trying to make a living. It’s not like I’m killing or robbing you. I’m just exercising my rights to try to sell you something. It’s a free country and your telephone number is listed, so what’s the problem.

Me: Sigh… never mind. I’m hanging up now.

Drone: Thanks for wasting my time with your stupid question!

Of course, the words and tone exhibited by your drone may be different from mine but the sentiment will be the same – nobody’s being hurt. But is it true that the drone’s cold call isn’t harming me? The answer is clearly no. Even when I decline to answer, the telemarketing intrusion kills a portion of my time that could have been spent on something more enjoyable or productive. It robs me of concentration; disrupting my thoughts and actions. It also wastes valuable bandwidth that could be used on all sorts of better things, like emergency calls, long enjoyable conversations between friends, and so. Leaving the cellphone off or unattended fixes these problems by running the risk of missing important calls and depriving one of the enjoyment that cellphone brings. In short, these telemarketing calls exact a tangible cost from the receiver, even if that cost can’t be precisely monetized.

In the most extreme case, where every telemarketer calls everyone in a single area code, there is even the possibility of a denial of service attack that would put people’s lives at risk. So, even though it may be a free country, the actions of these marketing drones aren’t free of what economists call negative externalities.

Recently, I escaped these costs, ever so briefly, by journeying south of the equator to visit family in Peru. Unfortunately, I landed in a collective economic situation that had an equally high negative outcome: the traffic of Lima. In case you’ve never had the (bad) chance to experience this, hardly any main avenue or road is absent bumper-to-bumper traffic at almost all hours. The skill and bravery exhibited by the average driver is as epic as the congestion is dense. Crisscrossing cars narrowly missing each other; horns honking at irregular intervals; drivers on motorcycles weaving between lanes – these are the common road motifs.

It’s worth considering how this situation has come about. The average motorist clearly is working under two basic rules. First, he needs to get somewhere in the least amount of time; after all his time is valuable. Second, his fellow drivers are working at cross purposes to him, since they are obviously trying to get where they are going as fast as possible as well. Therefore, he can only trust himself and must drive in a dog-eat-dog fashion. As a result, each driver is willing to break lane discipline at a drop of a hat, cross multiple lines of traffic to make a sudden turn right turn from the far most left lane, and look for any way to get from here to there without regard to the effect his actions have on those around him.

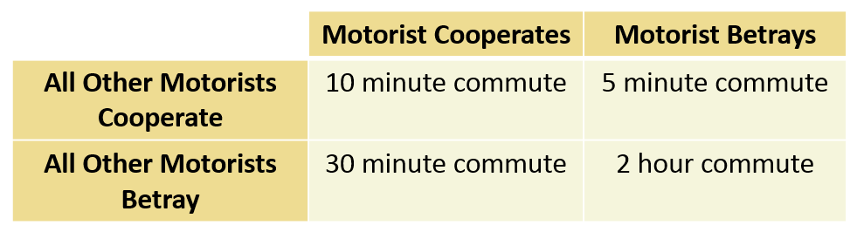

There is a prisoners-dilemma dimension to this whole scenario. Each motorist can choose to cooperate or to betray his fellows. Cooperation would entail politeness, sharing of the road, and allowing others to get in front – all at the expense of a slightly longer commute. Betrayal would entail ruthlessly cutting other drivers off to get ahead, abruptly changing lanes to jockey for position, and other assorted chicanery – all for the benefit of making the commute short. Of course, if all the drivers could be convinced to cooperate then the payout for each would not be as great as it would be for only one betrayal, but it would be much better than if all of them resort to the ‘every man for himself’ approach. A hypothetical payout table for such a scenario illustrates the point.

In both cases, cellphone telemarketing and congested traffic, the lack of awareness of how one’s actions lead to negative externalities for others, leads to what economists call the tragedy of the commons. The Wikipedia article summarizes the tragedy of the commons as:

All in all, this isn’t a bad description. It does lack in one important way. The individual users do act independently but not in their own self-interest. Rather they act in what they locally perceive as their best interest – as if all other users are somehow stupider than they are. As a result, they betray not only all the other users but their own best interest as well. And the truly sad part of this realization is that it isn’t clear at all how to improve the situation without properly educating and persuasively arguing for cooperation.