One of the most puzzling aspects of the last 10 or so years of economic and political discourse in the United States is the growing affection towards socialism and collectivism. Forget the obvious historical lessons that the former soviet bloc taught the world about the failures and incompetencies of socialism. After all, the Berlin wall fell in 1990 and the Soviet Union dissolved just over a year later – events far too distant in the past to resonate with a culture habituated to instant gratification. What boggles the mind is how the social-media generation can look past the ongoing misery in North Korea or Cuba

and the incredible collapse of Venezuela. These events are happening in the here-and-now and, surely, should be part of the digital discussion.

I’ve often wondered how to explain the discrepancy between the ‘slights’ that draw public attention to the ‘benefits’ of socialism (free college being a recent favorite) and the serious and wide spread problems that show the deep social and economic costs of that system. How can relatively small first-world issue, such as the pain of student debt, dominate the social media sphere while reports of widespread misery, such as interviews with average Cubans, who report that new toilets typically cost 2 years of wages, receive almost no attention? Is it a product of willful ignorance, poor education, fear of new ideas outside the comfort zone, myopic focus on self at the expense of others, simple unawareness, or some combination of these? And while I don’t expect that one answer will apply in every situation, I am convinced that most cases are largely explained by a poor education and an over-emphasis of the self at the expense of neighbors.

Oddly enough, I think this conclusion is strongly supported by the large and growing popularity in board games. This idea occurred to me over the recent Christmas holiday when I had ample time to play lots of board games with economically savvy friends. Many of the situations that arose drew snarky comments about the economic leanings of the game designers, how particular moves smacked of socialism, and so on.

Let there be no mistake, I am a fan of board games, especially the European style games like Catan, Princes of Florence, Ticket to Ride, and so on. Board games are a favorite pastime at my household and the holidays always afford ample time to gather everyone together to play. Ordinarily, I analyze the game mechanics and strategy in a bid to win, but due to the many comments flying around, I began to think about board games within a greater context.

I began to realize that, while they are fun, many board games may be contributing to the problem of economic ignorance rather than helping it. The reasons, in a nutshell, are two. First, a large majority of board games typically are built around an economic mechanic, such as growing a civilization or increasing trade, and provide players with a bank from which to draw funds periodically during the game. The bank comes as starting equipment with no recognition what the money contained represents nor where it comes from. Second, board games are often adversarial and zero-sum, in which the gain of one character comes at the expense of the others.

These two notions fly in the face of economic realities. As I’ve covered elsewhere, money in banks are not simple piles of currency used to prime the pump at the ‘beginning of the game’. Money represents the storehouses of the collective labor/time and expertise of untold numbers of people who have come before. We draw on this collected effort every time we get a loan, draw a dividend, or receive interest. We contribute to the pool every time we buy stock or make a deposit in our accounts. As a society, we grow wealth together, a point best exemplified by the parable of the pencil – which brings us to the second point.

As the rule, not the exception, we benefit by cooperation and not by competition. We not only draw on the collected financial wealth of our society but also on its collected intellectual wealth. Specialization and the division of labor can’t work without each of us sharing our talents and expertise with each other. This observation is not meant to dissuade one from the idea that competition is bad – it is not. Competition is the mechanism by which we decide on those goods and services that best serve society; but it needs to be recognized for what it is – an essential ingredient for vetting new ideas against old – but not the norm for everyday life.

At this point, we can return to the central conjecture that board games contribute to the overall misinformation of how the economy truly works that many people suffer from. As a case in point, consider one of our current favorites, the game called Machi Koro.

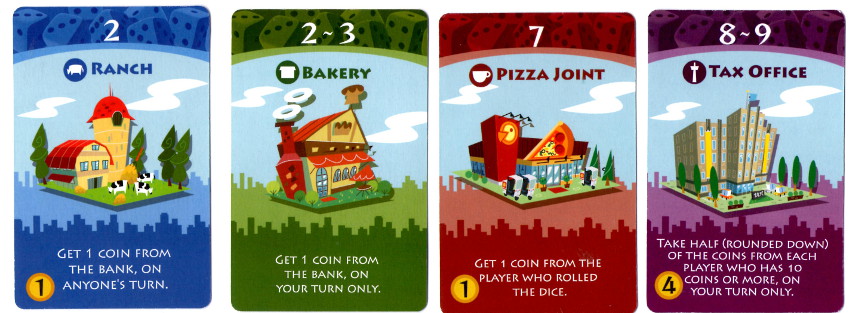

The basic theme of the game is that each player has just been elected mayor of a small town (that’s what machi koro means) and their goal is to grow the town into the largest city in the region by building developments and public works and by ‘stealing’ from the neighboring coffers. The game mechanic is built around the payout that these investments yield when the active player roles a die or dice. The investments come in four types, designated by their background color. Blue investments payout upon any matching role while green ones only yield an income when the active player gets a match. The payouts come from the bank with no connection as to why the investment produced a return. Red and purple investments operate analogously to the blue and green, with activation coming either on any turn or from the active player, respectively, with one difference. The resulting money comes not from the bank but from one’s opponents.

The red investments feature mostly eating establishments with names like Sushi Bar, Café, and Pizza Joint. The idea being that the unlucky player who activated them on his role is being charged for eating out. As bad as the red properties are, the purple investments are far more debilitating. Featuring large public works with names like Publisher and Tax Office, the purple properties can positively cripple your economy. Since they activate last in priority, a purple establishment can take profit out of a player’s hands seconds after it is earned.

Don’t get me wrong, Machi Koro is absolutely fun and I highly recommend it, but it is a poor model for the economy. Each player is not required to do anything to earn the money that comes their way. No customers exist whose needs must be satisfied, no voters must be courted, no supply chains, no production tradeoffs, no distributing or marketing of goods – in short no cooperation with anything or anyone else. Of course, it is the competition that makes it fun to play but, under no circumstances should it be thought of as a model for the real thing. Perhaps the only thing it gets correct, is the burdensome nature of taxes and crony capitalism.

So, what to do about board games? Well, it is important to recognize that the games that are popular are so because they reflect something we like. They reflect our ideas and values rather than causing them. So, continue to play them and have fun. And if you can slip into some discussion about how the economy really works then you’ll be a winner regardless of the final score.