This Thanksgiving I thought I would focus on an aspect of the economy, one for which I am extremely thankful and which doesn’t get a whole lot of attention: the division of labor. For the past several Thanksgivings, this column has focused on the lessons of private property that the pilgrims experienced (the hard way) as they tried to setup a life in the new world. This time around, I thought it would be appropriate to examine the division of labor as one of the central pieces that make up a voluntary economy.

I’m not sure where the division of labor was first noted in the historical record, but it is clear that human society has organized itself for millennia around the idea of a person training to learn a set of narrowly-defined skills and then working within a ‘trade’ that allows them to apply those skills effectively. There are at least three basic, fundamental reasons for why specialization helps.

First there is always a setup, an overall cost for getting things in order. This cost includes the time spent on the learning curve wherein the tradesman learns the specific set of skills required and the capital required to support the activities. Since it is a non-reoccurring cost it will be ‘cheaper’ when amortized over a large number of the same tasks. This ensures that the cost passed on to the consumer will be smaller, and thus more economical, when spread over multiple items. The only way to realize these per-unit savings is to have experts devote their time to reaping this benefit.

Second, there is the fact that with practice comes speed. A person who focuses his time on a limited set of tasks becomes much faster, since he is not distracted with the need to ‘change gears’ in his thinking or actions. The increased speed results largely from the fact that the uncertainty and the wrestling with what to do and when is taken out of the activity. An excellent example of this is the speed that results from someone who knows how to type using all ten fingers compared with the hunt-and-peck typist. The net result is an improvement in overall productivity.

The third reason that specialization thrives is that with practice also comes innovation. The expert has a chance to see the same operations over and over; to experience what works well and where improvements in the process can be made. As a result, new techniques, materials, or processes and organizations are more likely to occur to the expert compared with someone only tangentially familiar with the trade.

Adam Smith noted the amazing effects of the division of labor in his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (which most people shorten to simply The Wealth of Nations). In Chapter 1, Smith notes:

A conservative estimate of the gain that results from this specialization is to over-estimate the non-experts output at 10 pins/day and to under-estimate the 10-man factory at 40,000 pins. The gain is then a factor of 400 per person. This is but one aspect of what can be achieved by the division of labor guided by what Smith termed the Invisible Hand; the social benefits that result from individual pursuit by members of an economy of their own rational best-interests.

There is an interesting consequence that results from the division of labor; no man really knows how to make anything. By this is meant that no man can really know how to start purely from natural resources and, by expending his time, effort, and knowledge, build even the most modest of modern objects that society as a whole takes for granted.

In a famous essay entitled I Pencil, Leonard E. Read explores the complex set of operations, events, processes, and connections required to make something so ‘mundane’ as a pencil. Written in 1958, the essay emphasizes four points about the pencil and, by extension, the economy as a whole: 1) its creation is contingent on innumerable products and services that precede it, 2) no single mind knows all of these products and services nor knows how to put them together, 3) its creation is a miracle of the Invisible Hand, and 4) that men and women can accomplish amazing things when free to try.

Unfortunately, the essay is a bit old fashioned in its language and lacks what is probably the most essential element in today’s modern, hyper-stimulated world: pictures. To this end, I thought it would be fun to try to give a visual interpretation.

So, start with the pencil:

nice, simple, no moving parts. And it is easy to build one of these, right? All one needs is wood, some graphite for the ‘lead’, a bucket of paint, some rubber for the eraser, and a bit of metal to hold it on the end.

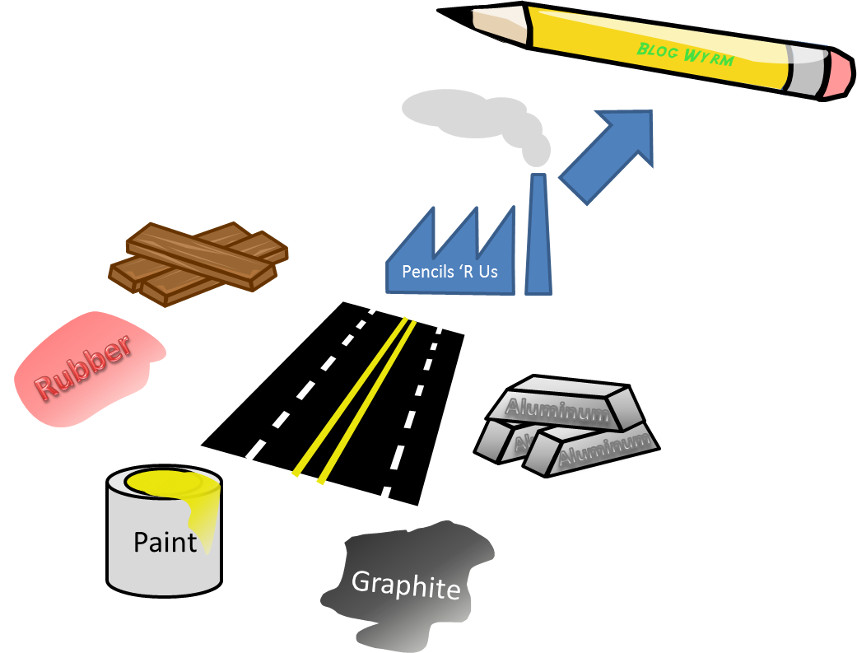

But wait! How does one put all these components together? One needs a factory. And how does one get the components to the factory? One needs a truck, and the roads upon which to drive, and fuel to power the engine.

And how does one get the truck? Well…, a truck is made of steel, iron, glass, copper, rubber, and so on. So one needs all these materials; a means to transport these materials from the factories that made them to the factory that builds the truck; fuel to power each factory and the trucks used to transport them (yep – you need trucks to build trucks). The number of linkages is truly mindbogglingly complex and intricate. And we actually haven’t even touched upon the services side of things, like operating a distribution network, running a store, or marketing and advertising.

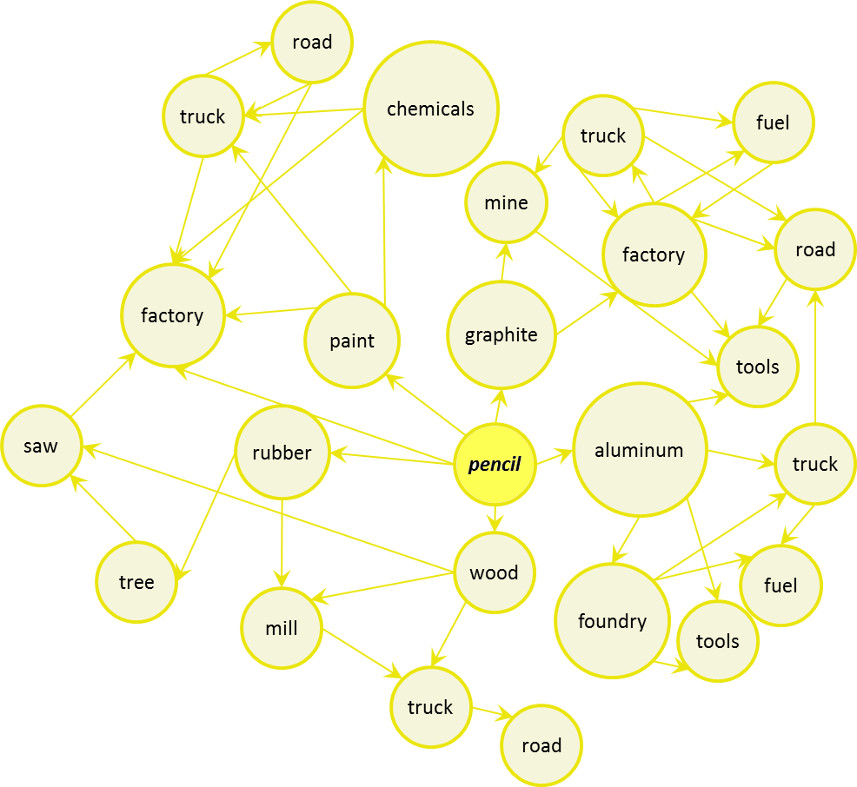

Even abstracting the pictures of the objects away until nothing is left besides labels and links doesn’t help in the final analysis. The following image is an attempt to capture only some (the barest few) of the most superficial connections, and it is already hopelessly complicated. The web-work of the economy is truly beyond the understanding of any human or group of humans.

And yet, there are some who think that the central planning can be done by a core group of wise and intelligent bureaucrats who are smarter than their fellow citizens. Those who think this way are not intelligent or honest enough to look at the interconnectedness of the economy and realize that it is beyond the scope of human understanding. As for me, I’ll continue to trust in the Invisible Hand and be thankful for it.