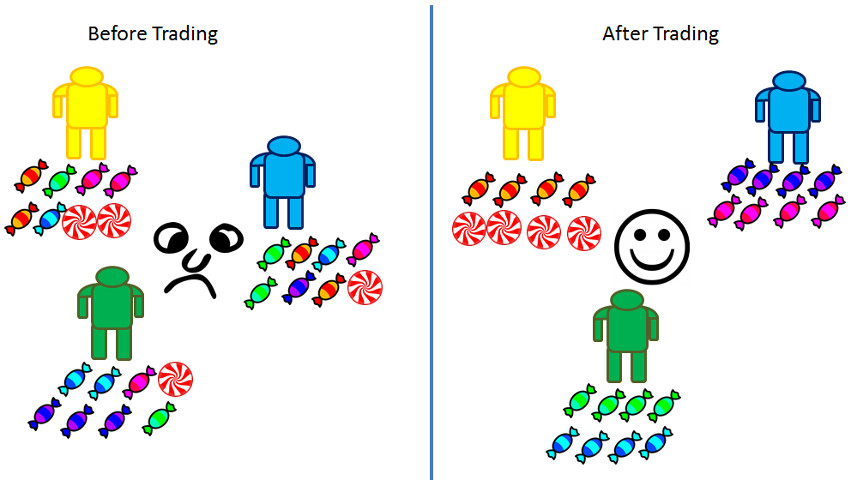

Last year around this time, I posted a column, entitled Candy and Wealth, where I explored what is meant by wealth. The basic premise is that wealth is built on an individual level – that one man’s garbage is another man’s treasure. The mechanism for proving this was the candy game where a variety of candies were distributed amongst a group of children at random. Before any trading was allowed, the children were asked about their satisfaction level. After being allowed to trade amongst themselves, the children were again asked about their satisfaction level and, even though the number of candies had not changed – only their distribution among the population, the satisfaction level across the board had risen.

In other columns, the notion that no party ever trades with another for parity has been discussed. In a nutshell, suppose that A has n goods and B has d dollars and that A and B agree to a transaction that trades their supplies. The fact that n goods were exchanged for d dollars does not mean that the value of the n goods was d dollars any more than it means that d dollars can buy n goods. A and B enter into a trade precisely because A believes that the d dollars are more valuable than the n goods and B, conversely, because he believes the n goods are more valuable than the d dollars. All trades work this way.

And yet how do we reconcile these ideas with the price and going market rates and bookkeeping that we see perpetually and ubiquitously around us? Simply put, the price and market rates are the sensations or nerve impulses in society as a whole that send messages of pleasure and pain to the body politic saying ‘do more of this’ or ‘stop producing that’ and so on. Bookkeeping acts as the collective memory of the previous transactions in addition to providing the required insight into entities such as publicly-traded corporations.

In no way, should those two ideas be confused, but in almost all circles that is precisely what we do.

Case in point is the book Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Created Modern Finance, by Jane Gleason-White.

Gleason-White opens and closes her book with a lament about the inadequacy of the GDP. Her view is that the GDP is an ‘all-important’ number that sets world-wide policy about how resources are valued, produced, and consumed and by whom but which fails to take into account the really important things about life. To quote Gleason-White:

I actually think she has a point here; that is to say that I agree with her conclusion. Unfortunately, I don’t agree with her argument that supports this conclusion nor do I agree with her solution. The reason being that she spends much of the book conflating the monetary value exchanged during a transaction with wealth in much the way I discussed above.

Central to her storyline is that the origin of these flawed numbers lies squarely with the invention and promulgation of double-entry bookkeeping, a feat of which she attributes the central role to a medieval monk by the name of Fra Luca Pacioli. For those who don’t know, double-entry bookkeeping is an accounting method whose inherent structure error-checks financial and capital transactions into which any enterprise enters. It is sort-of a monetary checksum whose ‘balance’ assures that no gross mistake has been made. It is to economics like what recorded measurements are to science; it is a way of keeping track.

There are many fine sources on the internet for examples of double-entry bookkeeping (my favorite is Accounting-Simplified.com’s treatment) and, while the concept is straightforward in theory, the intricacies can be difficult in practice. The situation is made more difficult by the fact that the particulars differ a bit between cultures. I’ll be focusing on the so-called Accounting Equation Approach, but all the methods have the same general feature.

The core concept in double-entry bookkeeping is that every transaction must have two accounts into which it is recorded – what I will call the ‘to’ and the ‘from’ account. It is much like a physics problem where energy or momentum of two colliding billiard balls is tracked. The gain in energy or momentum in one system is offset by an identical loss in the other, since energy and momentum are conserved.

For example, suppose I buy a computer and I pay for it with cash. To the untrained mind there is one transaction: the purchase of a computer. But under double-entry bookkeeping, there would be two accounts involved (thus double the entries). In the first account, I would add a debit to the assets account to show the acquisition of the machine and I would add a credit to the cash account to show the payment of money. The double-entry record would then look something like:

There is some ‘arcana’ (at least to me) as to when something is a debit versus a credit. This is where the Accounting Equation Approach gets its name as the following mnemonic (it’s not really an equation)

Assets – Liabilities = Capital

with debits having the following effects:

- Increase in assets

- Increase in expense

- Decrease in liability

- Decrease in equity

- Decrease in income

while credits reflect:

- Decrease in assets

- Decrease in expense

- Increase in liability

- Increase in equity

- Increase in income

I haven’t wrapped my brain around this schema and, fortunately, neither must you dear reader (unless you want to be a CPA). My critique of Gleason-White’s over-broadening of the pros and cons of double-entry bookkeeping can be understood with a simple example.

On the positive side, Gleason-While lauds double-entry bookkeeping as the enabling force of the Italian Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution (amongst other world events). She even suggests that there is a good case for saying that it gave rise to capitalism itself. On the negative side, she lays the corporate villainy of such bad actors as Enron, WorldCom, and the Royal Bank of Scotland (to name but a few) at the feet of this Venetian accounting style, presumably because they could ‘cook the books’ in a complicated way that was hard to detect. And, of course, she holds her central complaint about double-entry bookkeeping to the dehumanization of profit that it promotes (flawed numbers of GNP and GDP which rule our lives).

Before refuting these claims, it is interesting to note that she stays provocatively mum on the subject of how many corporations actually use double-entry bookkeeping without committing fraud. Perhaps she just assumes that they all do and we haven’t caught the others yet.

Now on to the refutation. And for this I will again return to the candy game. In the figure representing the candy trading game, each of our children would open an asset account to start and would debit it for eight pieces of candy, either by listing the different kinds separately (e.g. Yellow’s candy asset has 2 peppermints, 2 magenta, 2 orange, 1 green, and 1 cyan) or simply as eight pieces. In the credit account he might enter ‘time at school’ to account for how he came by his stash. After the trade, he would enter transactions that account for his trading 2 magenta, 1 green, and 1 cyan for 2 orange and 2 peppermint. The books must balance but nowhere is there a place to track that his enjoyment has increased. His increase in wealth is totally invisible to double-entry bookkeeping.

Suppose, instead, that money is used as a medium of exchange, and yellow sits on his candy stash (that’s why it is all hard candy – those things never go bad). Let’s say he waits until the pieces he wants have dropped in price and the pieces he has have gone up. The next transaction will show that his cash holding have increased but only a fool would say that that makes him wealthy. The real wealth comes in his enjoyment of the candies he likes and his real loss of wealth comes in the delayed gratification he endured while waiting for the finances to be in his favor.

Double-entry bookkeeping is blind to all of that structure, as well it should be. It is a memory of what has happened and not a measure of what is here and now. This realization makes Gleason-White’s assertion that only the accountants can saves us now ludicrous. No! Only proper economic thinking about the difference between wealth and money can help.