What do the terms ‘greedy capitalist’ and homo economicus have in common? Both terms are used, albeit with different connotations and by different groups, to describe a member of a society who pursues his own rational self-interest, trying to maximize it with each decision made. But what is rational self-interest? How do you define it? What is being maximized? And is the pursuit of one’s own self-interest necessarily incompatible with being a good neighbor? At the crux of these questions is the definition of rational self-interest.

Traditional economic analysis tends to view self-interest solely within the material context. Much like playing a board game, the success that you have had in maximizing your personal self-interest is completely judged by the amount of stuff you’ve accumulated. Cars, houses, jewelry, and money are all victory points that allow a person to rank themselves. You can declare yourself to have arrived at the good life when your house is bigger, your car more expensive, your jewelry more gaudy, and your bank account larger than the Joneses' down the street. In this view, a rational person never fails to make a decision that increases his material wealth. This, then, is the definition of homo economicus – an individual who tries to maximize his utility when he is a consumer, and his profit when he is a producer. You can go one step further in this description if you believe that the wealth one person enjoys is often or always at the expense of another. In this case, you would characterize a person pursuing his self-interest as a ‘greedy capitalist’.

But is this really how people act? It is true that we can find excellent examples of miserly, parsimonious, and bitter old men in literature. Scrooge in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Old Man Potter in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life come immediately to mind. And certainly there are people who take materialism too far, but does that mean that the system as a whole is corrupt or corrupting? I think not.

There is a fascinating game, in the sense of game theory, that is often used to determine the degree to which people will tend to maximize their utility by following their own rational self-interest. It’s called the Ultimatum Game.

It works essentially like this. The game begins when the game administrator (shown in blue below) approaches two random people with a pile of cash and invites them to play.

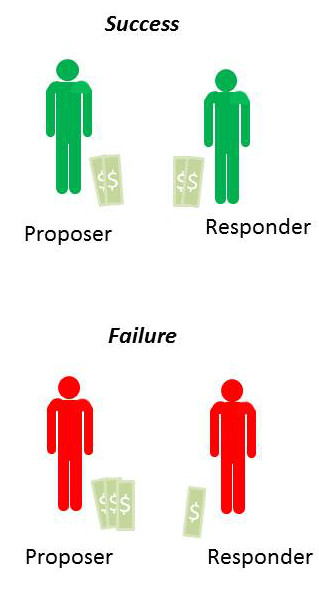

The rules are simple. The administrator will randomly designate one of them as the proposer and the other as the responder. The administrator will give the proposer the money and the proposer will decide on a split between himself and the responder. The responder’s only move is to decide to accept the proposal or reject it. If the responder accepts the proposal, they both get to keep the money in the proportions defined by the proposer. If the responder rejects the proposal he and the proposer walk away empty handed. The administrator emphasizes that the proposer gets only one chance to make an offer – there are no negotiations – and that this is the only time they will be playing this game.

Assuming that both players are homo economicus, the results of the game are easy to predict. The proposer should keep most of the money for himself and give only a small percentage, nearly zero, to the responder, because the proposer realizes that the responder will rationally maximize his own utility and will take any money offered. This way the responder will leave with more money than he had before the game began. The responder may lament the fact that the mere luck of the draw separates him from the proposer, but money is money, and free money is free money, and so he accepts.

When this game is run experimentally, the results are quite different. The responder accepts the split only when it is close to 50-50, and often rejects when the offer strays to far from an equal split. Furthermore, the proposer, without having the benefit of playing this game before, often offers a split close to the 50-50. Why do both participants often behave unlike homo economicus?

In practice, the experiment is done with more care and in a double blind fashion, as explained by the Foundation for Teaching Economics’ lesson plan found here. But the results remain the same.

- The mean split is 60-40 (proposer gets 60% and responder 40%)

- Most common split is 50-50

- About 20% of the offers that fall outside the ‘fair’ range are rejected.

How does one explain the proposer’s generosity? How does one understand why the responder ‘cuts off his nose to spite his face’ when the split is too low? As discussed in great detail in the accompanying appendix to the lesson plan, this game has been applied in a variety of circumstances where variations in age, gender, background and other factors have been examined and controlled. There appears to be no confounding variable that allows the administrator/experimenter to pre-determine when the participants will behave like homo economicus. Even the amount of money has been varied. Relatively vast amounts were brought to the developing world, where people subsist on only a few dollars a day, and the results remained the same.

A much more cogent explanation is that the definition of rational self-interest needs to be expanded from the materialistic realm to consider things like reputation, human compassion and altruism, and wisdom. And that these traits act to balance the purely materialistic instincts.

Virtue in the ancient world was defined not by a super-abundance of a trait but rather as the correct amount or a balance. A warrior who acted reckless and drove into battle with an overly great amount of physical courage was no more lauded than the coward who sat in the corner timidly, wanting for danger to pass by. The correct balance between caution and courage was the virtuous position.

Here in the ultimatum game, I see reflections of these ideas of virtue. The game results provide ample evidence that a human being engaged in a free market does not necessarily become selfish. The free exchange of goods and services is not inherently corrupting to those who participate, and they are no more likely to be preoccupied strictly with material possessions than if they had not engaged. The free market, like any tool, can be misused and can create an injustice, but it is not intrinsically flawed.

Lord Acton is famously quoted as saying “All power tends to corrupt; absolutely power corrupts absolutely”. I wonder what he would say about the Ultimatum Game. I’m not sure, but I like to believe that he would recognize the free marketplace as a place where people can come together to trade without the threat of coercion.